This article was brought to our attention by Guro Hospecio “Bud” Balani, Jr. As it turns out both his father, Hospecio Balbuena Balani, Sr., and his uncle, Martin D. Balbuena, were both members of the Regiment. He also had numerous uncles in the Regiment but to get their names, he’d have to dig deep into the darkest recesses of his mind, and it might get ugly in there. From what he understands, “The United States wanted to be at Regiment strength so they eventually merged the three Battalions into one unit and formed the 1st Filipino Regiment (keeping the First Unit’s Patch). Regiments are two or more Battalions, Battalions are three or more Companies. Companies are three or more Platoons. Platoons are three or more Squads. Squads are nine strong. These are just rough estimates. Also, any unit with the spelling of “Philippines” were US Army units that were recruited in the homeland. There were many Philippine Scout units, all in the Philippine islands. Any unit with the spelling of “Filipino”, was a unit formed in the United States, with the only units being Laging Una, Sulong and Bahala Na.”

Saturday, August 14th, 2004

The 1st and 2nd Filipino Infantry Regiments

By David T. Vivit, 1LT, AUS (Ret)

Laging Una – Sulung

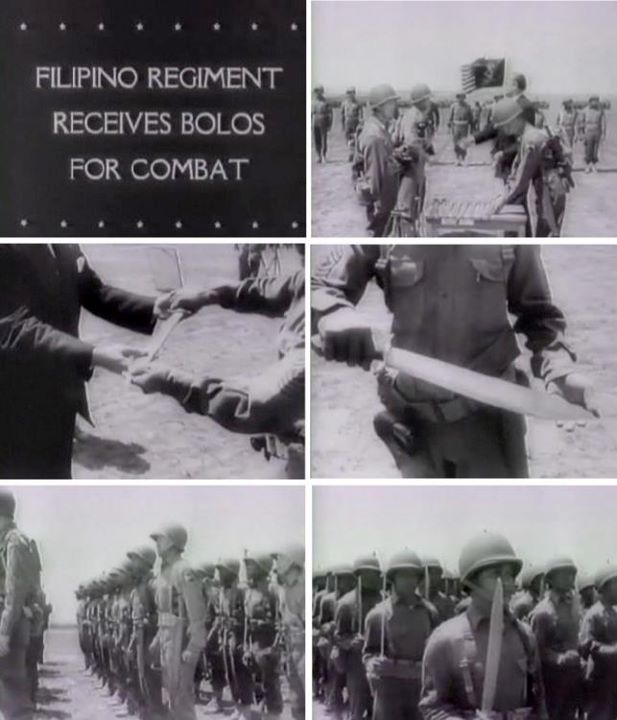

The 1st & 2nd (Laging Una – Sulung) Filipino Infantry Regiments were units of the Army of the United States (AUS) inducted into service during World War II. They were wholly manned by Filipino citizens in this country and Hawaii and officered by both Filipinos and Americans, the only non citizen units in the American Citizen Army. They were similar to the Philippine Scouts in that the latter were also wholly manned by Filipino citizens with both Filipino and American officers, but the similarities ended there. The Scouts were professional soldiers in the Philippine Department of the United States Regular Army (USA). Most of the men were married and enjoyed a high economic and social status in the Philippines in contrast to the mostly single discriminated against (in the U.S.) “laborers” and students of the Filipino Regiments. Each group of Filipino soldiers played important but different roles in World War II.

After the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor and Clark Field, Filipinos in the U.S. and Hawaii rushed to Army Recruiting Stations to enlist only to be rejected because they were not (US) citizens (Filipinos were not eligible for U.S. citizenship before the war). As residents, however, they were registered under the Draft Law, and when the first Filipino Battalion was activated in San Luis Obispo, California in April 1942, they “volunteered” for the draft instead of waiting for their call.

This unique unit was to spearhead MacArthur’s liberation forces when he returned to the Philippines. But the military authorities made a great miscalculation! In three months the 1st Filipino Battalion became the 1st Filipino Regiment, activated in Salinas on July 13, 1942 and on October 14th of the same year the 2nd Regiment was activated at Ft. Ord, bringing together a fighting force of more than 7,000 men. If created earlier, the Battalion very well could have become a Division. By the time it was activated hundreds had already joined the Navy and Army Air Corps. With an average age of over 30, they more than made up this overage by their spirit and enthusiasm. In no other units of the AUS in WWII, including the much publicized 442nd Regimental Combat Team (NISEI), was the motivation greater and the morale higher than in the 1st & 2nd Filipino Regiments. About the end of 1942 and in early 1943, these Filipino soldiers became American citizens under a new U.S Naturalization Law in mass oath taking ceremonies which made headlines throughout the country. After two years of intensive training in California without a single Court Martial case, these units went to New Guinea to prepare for their landings in the Philippines.

Here the 2nd Regiment was split up into the Counter-Intelligence Units (CIC), the Alamo Scouts and the Philippine Civil Affairs Unit (PCAU) all of which played important roles during the liberation.

The 1st Regiment remained intact as a combat team but for some unknown reason was not with the initial landing forces in Leyte. Instead it was relegated to the minor (but more dangerous against a fanatical enemy) role of mopping-up operations in Samar and Leyte. In accomplishing this difficult mission with minimum casualties, it earned the reputation of being the “most decorated regiment in the Pacific”. It remained for a “child” of the regiments, 1st Reconnaissance Battalion (Bahala Na) known only as “commandos” in the Philippines, whose operations during the occupation had been kept secret until recently, to really “spearhead MacArthur’s return to the Islands.” But this is a story in itself.

More significant than their military feats was their accomplishments in the field of romance. These gallant soldiers literally chased the shy, coy and above all, suspicious Filipino girls even as the war was going on. Having won them, they had to go through much Army red tape to get married. But marry they did and when the war was over, they brought their war brides back to the U.S. Those who didn’t have the patience for the hard to get “Pinays” came came back to the U.S. but later returned as civilians to bring back their post-war brides. Now it was for them to be regarded so highly, who before the war were looked down on so lowly. As respected U.S. citizens they settled down to bring up the second generation of Filipino Americans, many of whom have already served in Viet Nam in the spirit of the 1st and 2nd Filipino Infantry Regiments.

Bahala Na

This secret organization was conceived by General MacArthur and his staff even as they were being evacuated from the Philippines to Australia in March 1942. They knew that parts of the Islands remained under guerilla control and somehow a link must be established between them and his headquarters. The problem was where to procure the personnel for this “clandestine” unit, the nucleus of which was already in Australia with a handful of officers and men – patients and crew from a hospital ship – who volunteered to go back.

The problem was conveniently solved by the 1st and 2nd Filipino Regiments. In early 1943 Major General (then Colonel) Courtney Whitney, MacArthur’s closest adviser, came to the regiments to ask for volunteers. From among the many who volunteered, were picked the Filipino officers and men of this elite organization. Soon a few officers and men were sent directly to Australia to join the volunteers from the Philippines to form the 5217th Reconnaissance Battalion, “clandestine” which later became the 1st Reconnaissance Battalion (Special). They set up camp in Tagragalba just outside Beaudesert, fifty miles south of Brisbane. After weeks of training and operating under Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB) the first party was sent to the Philippines in October 1943.

Meanwhile, in California a group of enlisted men were sent to the Army Signal School at Camp Crowder, Missouri, from there they were sent to Australia to man the Signal Co., one of the two companies of the 5217th Battalion. A larger group of officers and men were sent to the Army Language School at the Presidio of Monterey. Here they learned elementary Japanese, Japanese ship and aircraft recognition and sailing. These were the officers and men who formed the other bigger company, the Reconnaissance Co. After three months this first big contingent of officers and men were shipped to Australia, arriving there in November 1943 just before the second party left for the Philippines. Other groups followed them from the Regiments through Monterey until the company was brought up to its authorized strength.

In Australia, with their war cry “Bahala Na” (Come What May!), they went through intensive and extensive training under the Australian Army. First they went to the tough jungle school of Canungra where they set new hiking endurance records through mosquito and leech infested mountains and rivers. From there they went to the equally tough SEA WARFARE School on Frazer Island where they learned swimming, underwater demolition, sabotage and guerilla tactics.

In July 1944, a cadre of one officer and five non-commissioned officers arrived from the 82nd Airborne Division in Italy to train a group of men for a pre-invasion mission of sabotage and communication disruptions. Now hardened, the men were ready for the toughest of all their training. But they lacked adequate facilities and proper training aids (they improvised their own C-47 mock door and didn’t have a tower to practice jumping) and this coupled with the Australian pilot’s inexperience caused the large number of “casualties”, probably a record, in the first class’ qualifying jumps. But this didn’t daunt the volunteers, for the bigger second class fared better.

While all this training was going on , more parties were being sent to the Islands. Parties of ten to thirty officers and men were outfitted in Brisbane and flown to Darwin where they took the submarines – the same ones which evacuated President Quezon and his exiled Commonwealth Government and the gold bullion from Corregidor to the U.S. A few Philippine Army officers were brought back to Australia from the guerrilla bands to lead some of the parties back to the Islands.

There were nine parties sent, the last one in a Destroyer. This was the party that raised the American flag in Homonhom Island three days before MacArthur landed in Leyte on October 27, 1944. The eighth and last submarine was sunk without a survivor by our own planes in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the greatest Naval battle in history. The paratroopers who were supposed to be the last and biggest party were never dropped because the invasion was advanced two months ahead of the original MacArthur planned invasion in Mindanao.

After the long and dangerous voyage through the Japanese blockade, the submarines landed in guerrilla controlled areas (as depicted in the motion picture “Back to Bataan”), although in some cases the reception was not quite as pleasant as in the picture. But this was the best part of this mission. After landing, the soldiers became civilians and disguised as fishermen, they fanned out through the length and breadth of the Islands in sail or just plain row boats.

In co-operation with the guerrillas whom they supplied with much needed medicines, small arms, ammunition, food, cigarettes and that rare wartime commodity called whiskey (later they brought and circulated the “I Shall Return” magazine and the new and legal “Liberty” peso bills to further confuse the enemy) the men of the Signal Company set up radio stations while the men of the Recon Co., posing as fishermen, farmers, merchants, taxi and caretela drivers and mess boys working in Japanese officers clubs, including Yamashita’s, gathered the information. A few were caught and paid the supreme penalty meted out to spies. This information was sent to guerrilla headquarters in Mindanao which relayed it through Darwin and to MacArthur’s headquarters in Brisbane.

On this military intelligence was based MacArthur’s strategy for the invasion of the Islands. When he “returned” to Leyte, the 1st Reconnaissance Battalion’s mission was practically over. But the men didn’t stop there. They went on to supply important information which led to decisive battles and engaged in commando tactics, blowing up bridges and ammo dumps.

For their splendid accomplishments, the “Commandos” of the “Balaha Na!” Battalion earned General MacArthur’s individual and Unit Commendations and the U.S. Presidential Unit Citation. But curiously enough it was awarded the Philippine Presidential Unit Citation for it’s work in the Resistance Movement.

Because of the limited space in the submarines (started with three and ended up with one) which were loaded with supplies and because the invasion was advanced two months ahead, not all the officers and men saw action in the Philippines. It was for the Korean War to prove the mettle of these well trained but battle untested men. Besides two who were killed, that unexpected war produced four outstanding “Bahala Na!” officers, two of them paratroopers – all heroes in their own right.

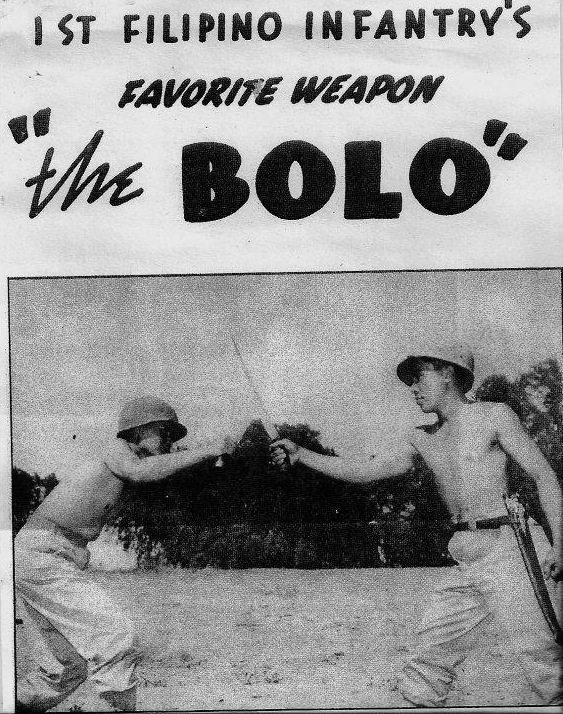

“Favorite weapon” photo courtesy of: http://www.watawat.net