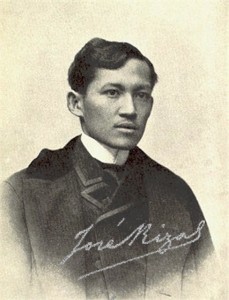

Imprinting Andres Bonifacio: The Iconization from Portrait to Peso by The Malacañan Palace Library Source: http://malacanang.gov.ph/2942-imprinting-andres-bonifacio-the-iconization-from-portrait-to-peso/Imprinting Andres Bonifacio: The Iconization from Portrait to Peso by The Malacañan Palace Library The face of the Philippine revolution is evasive, just like the freedom that eluded the man known as its leader. The only known photograph of Andres Bonifacio is housed in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, Spain. Some say that it was taken during his second wedding to Gregoria de Jesus in Katipunan ceremonial rites. It is dated 1896 from Chofre y Cia (precursor to today’s Cacho Hermanos printing firm), a prominent printing press and pioneer of lithographic printing in the country, based in Manila. The faded photograph, instead of being a precise representation of a specific historical figure, instead becomes a kind of Rorschach test, liable to conflicting impressions. Does the picture show the President of the Supreme Council of the Katipunan as a bourgeois everyman with nondescript, almost forgettable features? Or does it portray a dour piercing glare perpetually frozen in time, revealing a determined leader deep in contemplation, whose mind is clouded with thoughts of waging an armed struggle against a colonial power? Perhaps a less subjective and more fruitful avenue for investigation is to compare and contrast this earliest documented image with those that have referred to it, or even paid a curious homage to it, by substantially altering his faded features. This undated image of Bonifacio offers the closest resemblance to the Chofre y Cia version. As attested to by National Scientist Teodoro A. Agoncillo and the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, it is the image that depicts the well-known attribution of Bonifacio being of sangley (or Chinese) descent. While nearly identical in composition with the original, this second image shows him with a refined–even weak–chin, almond-shaped eyes, a less defined brow, and even modified hair. The blurring of his features, perhaps the result of the image being timeworn, offers little room for interjection. In contrast, the next image dating from a February 8, 1897 issue of La Ilustración Española y Americana, a Spanish-American weekly publication, features a heavily altered representation of Bonifacio at odds with the earlier depiction from Chofre y Cia. This modification catered to the Castilian idea of racial superiority, and to the waning Spanish Empire’s shock–perhaps even awe?–over what they must have viewed at the time as indio impudence. Hence the Bonifacio in this engraving is given a more pronounced set of features–a more prominent, almost ruthless jawline, deep-set eyes, a heavy, furrowed brow and a proud yet incongruously vacant stare. Far from the unassuming demeanor previously evidenced, there is an aura of unshakable, even obstinate, determination surrounding the revolutionary leader who remained resolute until his last breath. Notice also that for the first (although it would not be the last) time, he is formally clad in what appears to be a three-piece suit with a white bowtie–hardly the dress one would expect, given his allegedly humble beginnings. Given its printing, this is arguably the first depiction of Bonifacio to be circulated en masse. The same image appeared in Ramon Reyes Lala’s The Philippine Islands, which was published in 1899 by an American publishing house for distribution in the Philippines. The records of both the Filipinas Heritage Library and the Lopez Museum reveal a third, separate image of Bonifacio which appears in the December 7, 1910 issue of El Renacimiento Filipino, a Filipino publication during the early years of the American occupation. El Renacimiento Filipino portrays an idealized Bonifacio, taking even greater liberties with the Chofre y Cia portrait. There is both gentrification and romanticization at work here. His receding hairline draws attention to his wide forehead–pointing to cultural assumptions of the time that a broad brow denotes a powerful intellect–and his full lips are almost pouting. His cheekbones are more prominent and his eyes are given a curious, lidded, dreamy, even feminine emphasis, imbuing him with an air of otherworldly reserve–he appears unruffled and somber, almost languid: more poet than firebrand. It is difficult to imagine him as the Bonifacio admired, even idolized, by his countrymen for stirring battle cries and bold military tactics. He is clothed in a similar fashion to the La Ilustración Española y Americana portrait: with a significant deviation that would leave a telltale mark on succeeded images derived from this one. Gone is the white tie (itself an artistic assumption when the original image merely hinted at the possibility of some sort of neckwear), and in its stead, there is a … [Read more...]