Mandirigma.org Note:

Philippine Army fighting for Independence were referred to as “Insurgents” by the United States to justify their betrayal and invasion.

Site is still riddled with period U.S. propaganda.

https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/chronphil.html

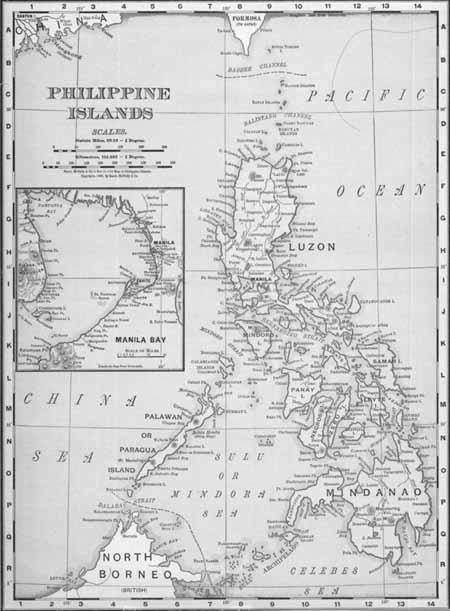

Chronology for the Philippine Islands and Guam in the Spanish-American War

1887

March

Publication in Berlin, Germany, of Noli Me Tangere (Touch Me Not) by José Rizal, the Philippines’ most illustrious son, awakened Filipino national consciousness.

1890

U.S. foreign policy is influenced by Alfred T. Mahan who wrote The Influence of Sea Power upon history, 1600-1783, which advocated the taking of the Caribbean Islands, Hawaii, and the Philippine Islands for bases to protect U.S. commerce, the building of a canal to enable fleet movement from ocean to ocean and the building of the Great White fleet of steam-driven armor plated battleships.

1892

July 3

La Liga Filipina, a political action group that sought reforms in the Spanish administration of the Philippines by peaceful means, was launched formally at a Tondo meeting by José Rizal upon his return to the Philippines from Europe and Hong Kong in June 1892. Rizal’s arrest three days later for possessing anti-friar bills and eventual banishment to Dapitan directly led to the demise of the Liga a year or so later.

July 7

Andrés Bonifacio formed the Katipunan, a secret, nationalistic fraternal brotherhood founded to bring about Filipino independence through armed revolution, at Manila. Bonifacio, an illiterate warehouse worker, believed that the Ligawas ineffective and too slow in bringing about the desired changes in government, and decided that only through force could the Philippines problem be resolved. The Katipunan replaced the peaceful civic association that Rizal had founded.

1895

January

Andrés Bonifacio elected supremo of the Katipunan, the secret revolutionary society.

March

Emilio Aguinaldo y Farmy joined Katipunan. He adopted the pseudonym Magdalo, after Mary Magdalene.

June 12

U.S. President Grover Cleveland proclaimed U.S. neutrality in the Cuban Insurrection.

1896

February 16

Spain implemented reconcentration (reconcentrado) policy in Cuba, a policy which required the population to move to central locations under Spanish military jurisdiction and the entire island was placed under martial law.

February 28

The U.S. Senate recognized Cuban belligerency with overwhelming passage of the joint John T. Morgan/Donald Cameron resolution calling for recognition of Cuban belligerency and Cuban independence. This resolution signaled to President Cleveland and Secretary of State Richard Olney that the Cuban crisis needed attention.

March 2

The U.S. House of Representatives passed decisively its own version of the Morgan-Cameron Resolution which called for the recognition of Cuban belligerency.

August 9

Great Britain foiled Spain’s attempt to gather European support of Spanish policies in Cuba.

August 26

Immediately following the Spanish discovery of the existence of the Katipunan, Andrés Bonifacio uttered the Grito de Balintawak, first cry of the Philippine Revolution. He called for the Philippine populace to revolt and to begin military operations against the Spanish colonial government.

December 7

U.S. President Grover Cleveland declared that the U.S. may take action in Cuba if Spain failed to resolve the Cuban crisis.

December 30

José Rizal was executed for sedition by a Spanish-backed Filipino firing squad on the Luneta, in Manila.

1896

William Warren Kimball, U.S. Naval Academy graduate and intelligence officer, completed a strategic study of the implications of war with Spain. His plan called for an operation to free Cuba through naval action, which included blockade, attacks on Manila, and attacks on the Spanish Mediterranean coast.

1897

March 4

Inauguration of U.S. President William McKinley.

March

Theodore Roosevelt was appointed assistant U.S. Secretary of the Navy. Emilio Aguinaldo was elected president of the new republic of the Philippines; Andrés Bonifacio was demoted to the director of the interior.

April 25

General Fernando Primo de Rivera y Sobremonte became governor-general of the Philippines, replacing General Camilo García de Polavieja; his adjutant was Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, his nephew.

May 10

Andrés Bonifacio, founder of the Katipunan revolutionary organization, was convicted of treason to the new republic and executed by order of fellow revolutionary Emilio Aguinaldo.

August 8

Spanish Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo was assassinated by the anarchist Miguel Angiolillo at Santa Agueda, Spain. Práxides Mateo Sagasta was made Spanish Prime Minister.

November 1

Emilio Aguinaldo succeeded in creating a Philippine revolutionary constitution and on the same date the Biak-na-Bato Republic was formed under the constitution as an effort at independence while the revolution gather momentum.

December 14-15

Spain reacted quickly to the Biak-na-Bato Republic and sought negotiations to end the war. With Pedro Paterno, a noted Filipino intellectual and lawyer, mediating, Aguinaldo representing the revolutionists and Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera representing the Spanish colonial government, the Pact of Biak-na-Bato was concluded. The Pact paid indemnities to the revolutionists the sum of 800,000 pesos, provided amnesty, and allowed for Aguinaldo and his entourage voluntary exile to Hong Kong.

December 31

Emilio Aguinaldo arrived in Hong Kong in exile under the terms of the Pact of Biak-na-Bato.

1898

February 8

Spain’s ambassador to the U.S., Enrique Dupuy de Lôme, resigned.

February 9

New York Journal published the confidential letter of Ambassador Enrique Dupuy de Lôme critical of President McKinley. The revelation of the letter helped push Spain and the United States toward war.

February 14

Luís Polo de Bernabé named Minister of Spain in Washington.

February 15

Explosion sank the battleship U.S.S. Maine in Havana harbor.

March 3

Governor-General of the Philippine Islands Fernando Primo de Rivera informed Spanish minister for the colonies Segismundo Moret y Prendergast that Commodore George Dewey had received orders to move on Manila.

March 9

U.S. Congress approved a credit of $50,000,000 for national defense.

March 17

Senator Redfield Proctor (Vermont) swayed Congress and the U.S. business community toward war with Spain. He had traveled at his own expense in February 1898 to Cuba to investigate the impact of the Spanish reconcentration (reconcentrado) policy on the island and returned to report to the Senate.

March 28

U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry published its findings that the battleship U.S.S. Maine was destroyed by mine.

March 29

The United States Government issued an ultimatum to the Spanish Government to terminate its presence in Cuba. Spain did not accept the ultimatum in its reply of April 1, 1898.

April

Governor-General of the Philippine Islands Fernando Primo de Rivera, in a surprise move, was replaced by Governor-General Basilo Augustín Dávila in early April. Upon his departure from the Philippines, the insurgent movement renewed revolutionary activity due mainly to the Spanish government’s failure to abide by the terms of the Pact of Biak-na-Bato.

April 4

The New York Journal issued a million copy press run dedicated to the war in Cuba. The newspaper called for the immediate U.S. entry into war with Spain.

April 11

The U.S. President William McKinley requested authorization from the U.S. Congress to intervene in Cuba, with the object of putting an end to the war between Cuban revolutionaries and Spain.

April 13

The U.S. Congress agreed to President McKinley’s request for intervention in Cuba, but without recognition of the Cuban Government.

The Spanish government declared that the sovereignity of Spain was jeopardized by U.S. policy and prepared a special budget for war expenses.

April 19

The U.S. Congress by vote of 311 to 6 in the House and 42 to 35 in the Senate adopted the Joint Resolution for war with Spain. Included in the Resolution was the Teller Amendment, named after Senator Henry Moore Teller (Colorado) which disclaimed any intention by the U.S. to exercise jurisdiction or control over Cuba except in a pacification role and promised to leave the island as soon as the war was over.

April 20

U.S. President William McKinley signed the Joint Resolution for war with Spain and the ultimatum was forwarded to Spain.

Spanish Minister to the United States Luís Polo de Bernabé demanded his passport and, along with the personnel of the Legation, left Washington for Canada.

April 21

The Spanish Government considered the U.S. Joint Resolution of April 20 a declaration of war. U.S. Minister in Madrid General Steward L. Woodford received his passport before presenting the ultimatum by the United States.

A state of war existed between Spain and the United States and all diplomatic relations were suspended. U.S. President William McKinley ordered a blockade of Cuba.

April 23

President McKinley called for 125,000 volunteers.

April 25

War was formally declared between Spain and the United States.

April 26

Willaim R. Day became U.S. Secretary of State.

April 29

The Portuguese government declared itself neutral in the conflict between Spain and the United States.

May 1

Opening with the famous quote “You may fire when your are ready, Gridley” U.S. Commodore George Dewey in six hours defeated the Spanish squadron, under Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón, in Manila Bay, the Philippines Islands. Dewey led the Asiatic Squadron of the U.S. Navy, which had been based in Hong Kong, in the attack. With the cruisers U.S.S. Olympia, Raleigh, Boston, and Baltimore, the gunboats Concord and Petrel and the revenue cutter McCulloch and reinforcements from cruiser U.S.S. Charleston and the monitors U.S.S. Monadnock and Monterey the U.S. Asiatic Squadron forced the capitulation of Manila. In the battle the entire Spanish squadron was sunk, including the cruisers María Cristina and Castilla, gunboats Don Antonio de Ulloa, Don Juan de Austria, Isla de Luzón, Isla de Cuba, Velasco, and Argos.

May 2

The U.S. Congress voted a war emergency credit increase of $34,625,725.

May 4

A joint resolution was introduced into the U.S. House of Representatives, with the support of President William McKinley, calling for the annexation of Hawaii.

May 10

Secretary of the Navy John D. Long issued orders to Captain Henry Glass, commander of the cruiser U.S.S. Charleston to capture Guam on the way to Manila.

May 11

Charles H. Allen succeeded Theodore Roosevelt as assistant secretary of the navy.

President William McKinley and his cabinet approve a State Department memorandum calling for Spanish cession of a suitable “coaling station”, presumably Manila. The Philippine Islands were to remain Spanish possessions.

May 18

Prime Minister Sagasta formed the new Spanish cabinet. U.S. President McKinley ordered a military expedition, headed by Major General Wesley Merritt, to complete the elimination of Spanish forces in the Philippines, to occupy the islands, and to provide security and order to the inhabitants.

May 19

Emilio Aguinaldo returned to Manila, the Philippine Islands, from exile in Hong Kong. The United States had invited him back from exile, hoping that Aguinaldo would rally the Filipinos against the Spanish colonial government.

May 24

With himself as the dictator, Emilio Aguinaldo established a dictatorial government, replacing the revolutionary government, due to the chaotic conditions he found in the Philippines upon his return.

May 25

First U.S. troops were sent from San Francisco to the Philippine Islands. Thomas McArthur Anderson commanded the vanguard of the Philippine Expeditionary Force (Eighth Army Corps), which arrived at Cavite, Philippine Islands on June 1.

June-October

U.S. business and government circles united around a policy of retaining all or part of the Philippines.

June 3

President McKinley broadened U.S. position to include an island in the Marianas, as a strategic link in the route from the United States to the Pacific Coast of Asia.

June 11

McKinley administration reactivated debate in Congress on Hawaiian annexation, using the argument that “we must have Hawaii to help us get our share of China.”

June 12

Emilio Aguinaldo declared Philippine Island independence from Spain. German squadron under Admiral Dieterichs arrived at Manila.

June 14

McKinley administration decided not to return the Philippine Islands to Spain.

June 15

Congress passed the Hawaii annexation resolution, 209-91. On July 6, the U.S. Senate affirmed the measure.

American Anti-imperialist League was organized in opposition to the annexation of the Philippine Islands. Among its members were Andrew Carnegie, Mark Twain, William James, David Starr Jordan, and Samuel Gompers. George S. Boutwell, former secretary of the treasury and Massachusetts senator, served as president of the League.

Admiral Dewey’s defeat of the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay on May 1, 1898 ignited impassioned nationalistic feelings in Spain. Spanish Admiral Manuel de la Cámara y Libermoore’s squadron received orders to relieve the Spanish garrison in the Philippine Islands. His fleet consisted of the battleship Pelayo, the armored cruiser Carlos V, the cruisers Rápido and Patriota, the torpedo boats Audaz, Osado, and Proserpina, and the transports Isla de Panay, San Francisco, Cristóbal Colón, Covadonga, and Buenos Aires.

June 16

Admiral Cámara y Libermoore’s fleet set sail from Spain. Efforts were made by United States’ representatives to impede the progress of the fleet, by protesting the coaling of the fleet in neutral ports. The Spanish fleet was denied coaling at Port Said, at the entrance to the Suez Canal.

June 18

U.S. Secretary of the Navy John D. Long ordered Commodore William T. Sampson to create a new squadron, the Eastern Squadron, for possible raiding and bombardment missions along the coasts of Spain.

June 20

Spanish authorities surrendered Guam to Captain Henry Glass and his forces on the cruiser U.S.S. Charleston.

June 23

A revolutionary governent with Emilio Aguinaldo as its president again was established, the second such government in Philippine history, replacing the dictatorial government created by Aguinaldo a month earlier.

July 1

Philippine revolutionists began the siege of the Spanish garrison at Baler, Luzon, Philippine Islands.

July 7

Spanish Admiral Cámara y Libermoore’s fleet was ordered back to Spain.

U.S. President McKinley signed the Hawaii annexation resolution, following its passage in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate.

July 18

The Spanish government, through the French Ambassador to the United States, Jules Cambon, initiated a message to President McKinley to suspend the hostilities and to start the negotiations to end the war. Duque de Almodóvar del Río (Juan Manuel Sánchez y Gutiérrez de Castro), Spanish Minister of State, directed a telegram to the Spanish Ambassador in Paris charging him to solicit the good offices of the French Government to negotiate a suspension of hostilities as a preliminary to final negotiations.

July 25

General Wesley Merritt, commander of Eighth Corps, U.S. Expeditionary Force, arrived in the Philippine Islands.

July 26

French Government contacted the United States Government regarding the call for suspension of hostilities at the request of the Spanish Government.

July 30

U.S. President McKinley and his Cabinet submitted to Ambassador Cambon a counter-proposal to the Spanish request for ceasefire.

August 2

Spain accepted the U.S. proposals for peace, with certain reservations regarding the Philippine Islands. McKinley called for a preliminary protocol from Spain before suspension of hostilities. That document was used as the basis for discussion between Spain and the United States at the Treaty of Peace in Paris.

August 7

Emilio Aguinaldo instructed Felipe Agoncillo, the Philippine revolutionaries’ special emissary to President McKinley, to publish the “Act of Proclamation” and the “Manifesto to Foreign Governments” in the Hong Kong papers.

August 12

Peace protocol that ended all hostilities between Spain and the United States in the war fronts of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines was signed in Washington, D.C.

August 13

The United States troops “took” Manila, a day after the Armistice was signed in Washington, D.C. In upholding Spain’s honor, Governor-General Fermín Jáudenes y Álvarez, realizing that the Spanish forces were no match for the invading Americans, negotiated a secret agreement with Americans General Merritt and Admiral Dewey, with Belgian consul Edouard Andre mediating. The secret agreement, unknown to the Filipinos at the time, involved the staging of a mock battle between Spanish and American forces intentionally to keep Filipino insurgents out of the picture. Once the pre-agreed attack began, the Spaniards, on cue, hoisted a white flag of capitulation and American troops filed into the city orderly and quietly with very little bloodshed. The Spaniards were only too eager to hand over the Philippines to the Americans. Admiral Dewey, for his part, never intended to hand the Philipines over to the “undisciplined insurgents”. Thus, the Philippines became a possession of the United States and the seeds of Philippine insurrection were sown.

August 14

Capitulation was signed at Manila and U.S. General Wesley Merritt established a military government in the city, with himself serving as first military governor.

August 15

U.S. General Arthur MacArthur appointed military commandant of Manila and its suburbs.

September 13

The Spanish Cortes (legislature) ratified the Protocol of Peace.

September 15

The inaugural session of the Congress of the First Philippine Republic, also known as the Malolos Congress, was held at Barasoain Church in Malolos, province of Bulacan, for the purpose of drafting the constitution of the new republic.

September 16

The Spanish and U.S. Commissioners for the Peace Treaty were appointed. U.S. Commissioners were William R. Day (U.S. Secretary of State), William P. Frye (President pro tempore of Senate, Republican-Maine), Whitelaw Reid, George Gray (Senator, Democrat- Delaware), and Cushman K. Davis (Chairman, Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Republican-Minnesota). The Spanish Commissioners were Eugenio Montero Ríos (President, Spanish Senate), Buenaventura Abarzuza (Senator), José de Garnica y Diaz (Associate Justice of the Supreme Court), Wenceslao Ramírez de Villa Urrutia (Envoy Extraordinary), and Rafael Cerero y Saenz (General of the Army).

William R. Day resigned as U.S. Secretary of State and was succeeded by John Hay.

October 1

The Spanish and United States Commissioners convened their first meeting in Paris to reach a final Treaty of Peace.

Felipe Agoncillo, representative of President Emilio Aguinaldo, presented his case in Washington for the Philippine Independence movement and its representation on the Peace Commission. His request was rejected by President McKinley because the First Philippine Republic was not recognized by foreign governments.

October 25

McKinley instructed the U.S. peace delegation to insist on the annexation of the Philippines in the peace talks.

November 17

The Revolutionary Government of the Visayas, Philippine Islands, was proclaimed; a United States force stood poised to capture the city.

November 28

The Spanish Commission for Peace accepted the United States’ demands in the Peace Treaty.

November 29

The Philippine revolutionary congress approved a constitution for the new Philippine Republic.

December 1

The Philippine revolutionists declared their fight for the independence of their islands.

December 10

Representatitves of Spain and the United States signed the Treaty of Peace in Paris. Spain renounced all rights to Cuba and allowed an independent Cuba, ceded Puerto Rico and the island of Guam to the United States, gave up its possessions in the West Indies, and sold the Philippine Islands, receiving in exchange $20,000,000.

December 21

President McKinley issued his Benevolent Assimilation Proclamation, ceding the Philippines to the United States, and instructing the American occupying army to use force, as necessary, to impose American sovereignity over the Philippines even before he obtained Senate ratification of the peace treaty with Spain.

1899

January 1

Emilio Aguinaldo was declared president of the new Philippine Republic, following the meeting of a constitutional convention. United States authorities refused to recognize the new government.

January 4

President McKinley’s proclamation of December 21, 1898, declaring U.S. policy in the Philippine Islands as one of “benevolent assimilation” in which “mild sway of justice and right” would be substituted for “arbitrary rule,” was published in the Philippine Islands. Aguinaldo issued his own proclamation that condemned “violent and aggressive seizure” by the United States and threatened war.

January 17

U.S. annexed Wake Island for use as cable link to the Philippine Islands. U.S. Commander Edward Taussig, U.S.S. Bennington, landed on the island and claimed it for the United States.

January 20

President William McKinley appointed the First Philippine Commission (the Schurman Commission), a five person group that included Jacob Schurman (President of Cornell University), Admiral Dewey and General Ewell S. Otis, to investigate conditions in the islands and to make recommendations as conditions worsened in Filipino-American relations.

January 21

The constitution of the Philippine Republic, the Malolos Constitution, was promulgated by the followers of Emilio Aguinaldo.

January 23

Inauguration of the First Philippine Republic at Barasoain Church, Malolos, in the province of Bulacan.

February 4

The Philippine Insurrection began as the Philippine Republic declared war on the United States forces in the Philippine Islands, following the killing of three Filipino soldiers by U.S. forces in a suburb of Manila.

February 6

U.S. Senate ratified the Treaty of Paris by a vote of 52 to 27.

March 19

The Queen regent of Spain, María Cristina, signed the Treaty of Paris, breaking the deadlock in the Spanish Cortes.

March 31

U.S. forces captured the Philippine revolutionary capital of Malolos.

April 11

The Treaty of Paris was proclaimed.

June 2

Spanish forces at Baler, Philippine Islands, under the command of Lieutenant Saturnino Martín Cerezo finally surrendered to the Philippine Revolutionary forces, following a siege that began on July 1.

June 12

First anniversay of Philippine independence as proclaimed by Aguinaldo in Kawit the year before.

August 20

U.S. General John C. Bates and the sultan of Sulu, Jamal-ul Kirim II, signed an agreement in which the U.S. pledged non-interference in Sulu.

November 12

Alarmed by mounting American military successes on the battlefields, Emilio Aguinaldo dissolved the regular revolutionary army and ordered the establishment of decentralized guerrilla commands in several military zones in the Philippine Islands.

December 2

General Gregorio del Pilar was killed in the battle of Tirad Pass by Americans pursuing the fleeing Aguinaldo.

1900

March 16

President William McKinley appointed the Second Philippine Commission (the Taft Commission) headed by William Howard Taft. Between September 1900 and August 1902, it issued 499 laws, a judicial system was established (including a Supreme Court), a legal code was written, and a civil service was organized.

1901

March 23

Led by General Frederick Funston, U.S. forces captured Emilio Aguinaldo on Palanan, Isabela Province. Later, he declared allegiance to the United States.

1902

July 1

The first organic act, known as the Philippine Bill of 1902, was passed by the U.S. Congress. It called for the management of Phillipine affairs, upon restoration of peace, by establishing the first elective Philippine Assembly and the Taft Commission comprising the lower and upper house, respectively, of the Philippine Legislature. The passage of the Act may be attributed in part to José Rizal and his stirring last farewell to his beloved country immortalized in his poem, Mi Ultimo Adios, that he wrote in his cell at Fort Santiago on the eve of his execution by the Spaniards on December 30, 1896. At first, there was strong opposition to the passage of the bill from misinformed members of the House, some of whom referred to the Filipinos as “barbarians” incapable of self government. Thereupon, Congressman Henry A. Cooper of Wisconsin took the floor and recited Rizal’s last farewell before a skeptical House. Silence soon pervaded the floor as Cooper, eyes moist with tears and voice deep with emotion, recited the poem stanza by stanza. Soon after his recitation, Cooper thunderously asked his colleagues might there be a future for such a barbaric, uncivilized people who had given the world a noble man as Rizal. The vote was taken on the bill, and passed the House.

July

War ended in the Philippines, with more than 4,200 U.S. soldiers, 20,000 Filipino soldiers, and 200,000 Filipino civilians dead.