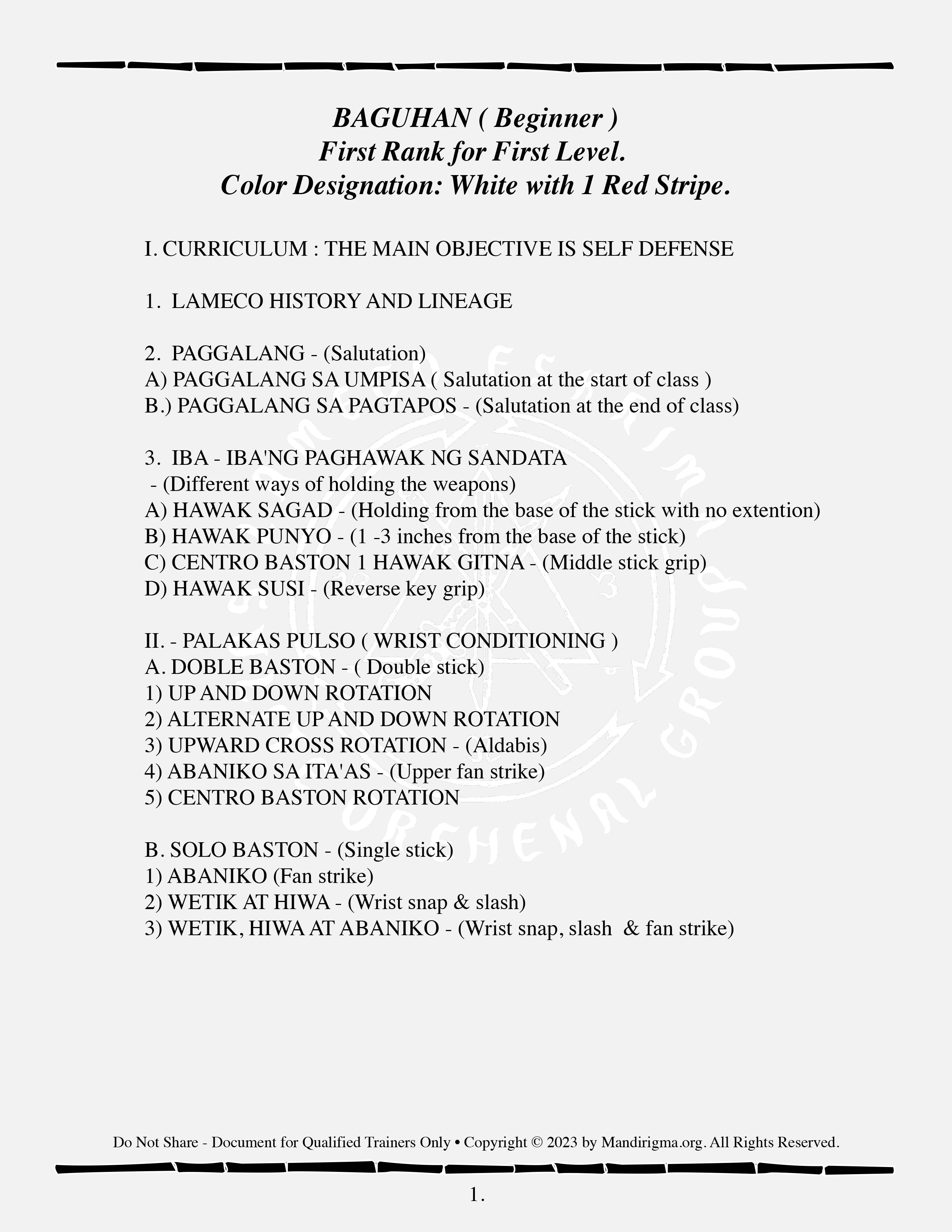

Photo: Members of “The Tinio Brigade”. Anti American Resistance in the Ilocos Provinces, 1899-190.

Staff: (to which Apolinario Querubin’s Guerilla 4 belonged) seated L to R: Captain Yldefonso Villareal, Brig. Gen. Benito Natividad, Brig. Gen. Manuel Tinio, Lt. Col. Joaquin Alejandrino and Maj. Joaquin Buencamino(son of Felipe Buencamino, a minister in the Aguinaldo cabinet); Standing L to R: 2lt. Francisco Natividad and two unidentified officers; Seated: the 15 year-old officer 2Lt. Pastor Alejandrino.

———

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manuel_Tinio

Manuel Tinio y Bundoc (June 17, 1877 – February 22, 1924) was the youngest General[2] of the Philippine Revolutionary Army, and was elected Governor[3] of the Province of Nueva Ecija, Republic of the Philippines in 1907. He is one of the three Fathers of the Cry of Nueva Ecija along with Pantaleon Valmonte and Mariano Llanera.

Manuel Tinio, then 18 years old, joined the Katipunan in April 1896. By August he had organized a company composed of friends, relatives and tenants. Personally leading his group of teenaged guerillas, he conducted raids and depredations against Spanish detachments and patrols in Nueva Ecija. Occasionally, he joined up with similar forces under other youthful leaders.

An Early flag of the Katipunan.

On September 2, 1896, Manuel Tinio and his men joined the combined forces of Mariano Llanera and Pantaleon Belmonte, capitanes municipales or mayors of Cabiao and Gapan, respectively, in the attack on San Isidro. Of 3,000 who volunteered, 500 determined men were chosen for the attack. Led by a bamboo orchestra or musikong bumbong of Cabiao, the force came in two separate columns from Cabiao and Gapan City and converged in Sitio Pulu, 5 km. from San Isidro. Despite the fact that they had only 100 rifles, they furiously fought the Spaniards holed up in the Casa Tribunal, the arsenal, other government buildings and in the houses of Spanish residents. Capt. Joaquin Machorro, commander of the Guardias Civiles, was killed on the first day of battle. According to Julio Tinio, Manuel’s cousin and a participant in the battle, Manuel had a conference in the arsenal with Antonio Luna and Eduardo Llanera, the general’s son, immediately after the battle.

The Spanish authorities hastily organized a company of 200 civilian Spaniards and mercenaries the following day and attacked the overconfident insurgents, driving the besiegers away from the government center. The next day more Spanish reinforcements arrived from Peñaranda, forcing the poorly armed rebels to retreat, leaving behind 60 dead. The Spaniards went in hot pursuit of the insurgents, forcing those from Cabiao to flee to Candaba, Pampanga, and those from Gapan to hide in San Miguel de Mayumo in Bulacan. The insurgents from San Isidro fled across the river to hide in Jaen. The relatives of those who were recognized were driven away from their homes by the colonial authorities. Manuel Tinio and his troop stayed to protect the mass of people from Calaba, San Isidro, who were all his kinfolk, hastening across the river to Jaen, Nueva Ecija.

The Spaniards’ relentless pursuit of the rebels forced them to disband and go into hiding until January 1897. Tinio was a special target. At 5 feet 7 inches (170 cm) tall, he literally stood out among the attackers, whose average height was below 5 feet (150 cm). He fled to Licab. A platoon of cazadores (footsoldiers) was sent to arrest him, forcing Hilario Tinio Yango, his first cousin and the Capitan Municipal of the town, to lead them to him. Warned of the approaching soldiers, Manuel again escaped and fled on foot back to San Isidro, where, in the barrios of Calaba, Alua and Sto. Cristo, he hid with relatives in their various farms beside the Rio Gapan (now known as the Peñaranda River). Fear of arrest compelled him to be forever on the move. He never slept in the same place. Later on, he would attribute his ill health in his middle age to the privations he endured during those months of living exposed to the elements.

The passionate rebels reorganized their forces the moment Spanish pursuit died down. Tinio and his men marched with Gen. Llanera in his sorties against the Spaniards. Llanera eventually made Tinio a Captain.

The aggressive exploits of the teen-aged Manuel Tinio reached the ears of General Emilio Aguinaldo, whose forces were being driven out of Cavite and Laguna, Philippines. He evacuated to Mount Puray in Montalban, Rizal and called for an assembly of patriots in June 1897. In that assembly, Aguinaldo appointed Mamerto Natividad, Jr. as commanding general of the revolutionary army and Mariano Llanera as vice-commander with the rank of Lt.-General. Manuel Tinio was commissioned a Colonel and served under Gen. Natividad.

The constant pressure from the army of Gov. Gen. Primo de Rivera drove Aguinaldo to Central Luzon. In August, Gen. Aguinaldo decided to move his force of 500 men to the caves of Biac-na-Bato in San Miguel, Bulacan because the area was easier to defend. There, his forces joined up with those of Gen. Llanera. With the help of Pedro Paterno, a prominent Philippines lawyer, Aguinaldo began negotiating a truce with the Spanish government in exchange for reforms, an indemnity, and safe conduct.

On August 27, 1897, Gen. Mamerto Natividad and Col. Manuel Tinio conducted raids in Carmen, Zaragoza and Peñaranda, Nueva Ecija. Three days later, on the 30th, they stormed and captured Santor (now Bongabon) with the help of the townspeople. They stayed in that town till September 3.

On September 4, with the principal objective of acquiring provisions lacking in Biac-na-Bato, Gen. Natividad and Col. Manuel Tinio united their forces with those of Col. Casimiro Tinio, Gen. Pío del Pilar, Col. Jose Paua and Eduardo Llanera for a dawn attack on Aliaga. (Casimiro Tinio, popularly known as ‘Capitan Berong’, was an elder brother of Manuel through his father’s first marriage.)

Thus began the Battle of Aliaga, considered one of the most glorious battles of the rebellion. The rebel forces took the church and convent, the Casa Tribunal and other government buildings. The commander of the Spanish detachment died in the first moments of fighting, while those who survived were locked up in the thick-walled jail. The rebels then proceeded to entrench themselves and fortify several houses. The following day, Sunday the 5th, the church and convent as well as a group of houses were put to the torch due to exigencies of defense.

Spanish Governor General Primo de Rivera fielded 8,000 Spanish troops under the commands of Gen. Ricardo Monet and Gen. Nuñez in an effort to recapture the town. A column of reinforcements under the latter’s command arrived in the afternoon of September 6. They were met with such a tremendous hail of bullets that the general, two captains and many soldiers were wounded, forcing the Spaniards to retreat a kilometer away from the town to await the arrival of Gen. Monet and his men. Even with the reinforcements, the Spaniards were overly cautious in attacking the insurgents. When they did so the next day, they found the town already abandoned by the rebels who had gone back to Biac-na-Bato. Filipino casualties numbered 8 dead and 10 wounded.

Gen. Natividad and Col. Manuel Tinio shifted to guerrilla warfare. The following October with full force they attacked San Rafael, Bulacan to get much-needed provisions for Biac-na-Bato. The battle lasted several days and, after getting what they came for, they left a detachment in Bo. Kaingin to hold back the Spanish reinforcements from Baliwag, Bulacan. To divert Spanish forces from Nueva Ecija, Natividad and Tinio attacked Tayug, Pangasinan on Oct. 4, 1897, occupying the church in the heart of the poblacion.

Meanwhile, peace negotiations continued and in October Aguinaldo gathered together his generals to convene a constitutional assembly. On Nov. 1, 1897 the Constitution was unanimously approved and on that day the Biac-na-Bato Republic was established.

However, Gen. Natividad, who believed in the revolution, opposed the peace negotiations and continued to fight indefatigably from Biac-na-Bato. On Nov. 9, while leading a force of 200 men with Gen. Pío del Pilar and Col. Ignacio Paua, Natividad was killed in action in Entablado, Cabiao. Col. Manuel Tinio brought the corpse back to the general’s grieving wife in Biac-na-Bato. (Incidentally, Gen. Natividad’s widow, Trinidad, was the daughter of Casimiro Tinio–”Capitan Berong”.) With the death of the army’s commanding general, Col. Manuel Tinio was commissioned Brigadier General and designated as commanding general of operations on Nov. 20, 1897. Gen. Tinio, all of 20 years, became the youngest general of the Philippine Revolutionary Army. (Gregorio del Pilar, already 22, was only a Lt. Colonel at that time.)

On Dec. 20, 1897, the Pact of the Biac-na-Bato was ratified by the Assembly of Representatives. In accordance with the terms of the peace pact, Aguinaldo went to Sual, Pangasinan, where he and 26 members of the revolutionary government boarded a steamer to go into voluntary exile in Hongkong. The Novo-Ecijanos in the group were Manuel Tinio, Mariano and Eduardo Llanera, Benito and Joaquin Natividad, all signatories of the Constitution.

In Hongkong, the exiles agreed among themselves to live as a community and spend only the interest of the initial P400,000 the Spanish Government had paid in accordance with the Pact of the Biac-na-Bato. The principal was to be used for the purchase of arms for the continuation of the revolution at a future time. The Artacho faction, however, wanted to divide the funds of the Revolution among themselves. The Novo-Ecijanos did not vote with the opportunist Artacho ‘faction’, and, being relatively well off, thanks to a relative who provided them with funds (Trinidad Tinio vda. de Natividad), “they got a house where they lived like a republic”, as they said.

Would history have been different if the Spanish authorities had not reneged on the terms of the Pact and withheld the amount of P900,000 which was supposed to have been divided among non-combatants who had suffered in the fighting? Thus shortchanged, considering themselves no longer honor bound to lay down arms, the revolutionists rose again. Once again fighting broke out all over Luzon. In Nueva Ecija, the rebels captured the towns again one by one.

But American intervention was on the way. As early as February 1898 an American naval squadron had steamed into Manila Bay. On May 1, less than a week after the declaration of the Spanish–American War, the American naval squadron completely destroyed the Spanish fleet. Admiral Dewey of the United States of America immediately dispatched the revenue cutter “McCulloch” to Hongkong to fetch Aguinaldo, who returned to the Philippines on May 19. On May 21 Aguinaldo issued a proclamation asking the nation to rally behind him in a second attempt to obtain independence. Revolutionary leaders promptly stepped up their raids and ambuscades on Spanish garrisons in Central Luzon, capturing more than 5,000 prisoners. By the end of May, the whole of central and southern Luzon, except Manila, was practically in Filipino hands. Aguinaldo promptly established a Dictatorial Government on May 24, with himself as Supremo (supreme commander) and proclaimed Philippine Independence on June 12, 1898. Apolinario Mabini, however, prevailed upon Aguinaldo to decree the establishment of a Revolutionary Government on June 23.

Manuel Tinio and the rest of the revolutionists in Hongkong sailed for Cavite on June 6 on board the 60-ton contraband boat “Kwan Hoi” to join their Filipino leader. Upon his arrival in Cavite, Tinio was instructed to organize an expeditionary force to wrest the Ilocano provinces from Spanish hands. Thus would start the thrust into the North and its conquest by Novo-Ecijano General Manuel Tinio. First, he retrieved from Hagonoy, Bulacan 300 Mauser and Remington rifles that had been captured from the Spaniards and stored in that town. He then took the steamer to San Isidro, Nueva Ecija. Upon his arrival on June 13 he immediately set up 3 companies of 108 men each under the commands of Captains Joaquin Alejandrino, Jose Tombo and 1st Lt. Joaquin Natividad who was given overall command. All the officers were Novo-Ecijanos, except for Celerino Mangahas who hailed from Paombong, Bulacan.

On July 7, 1898 Aguinaldo reorganized the provincial government of Nueva Ecija and appointed Felino Cajucom as governor. The province was divided into four military zones:

- Zone 1 under Gen. Mariano Llanera with Gen. Tinio as deputy covered the towns of San Isidro, San Antonio, Jaén, Gapan and Peñaranda;

- Zone 2 under Pablo Padilla and Angelo San Pedro covered the towns of Cabanatuan, San Leonardo, Sta. Rosa, Sto. Domingo and Talavera;

- Zone 3 under Delfin Esquivel and Ambrosio Esteban covered the towns of Aliaga, Licab, Zaragoza, San Jose, San Juan de Guimba and Cuyapo;

- Zone 4 under Manuel Natividad and Francisco Nuñez covered the towns of Rosales, Nampicuan, Umingan, Balungao and San Quintin.

On June 19, Gen. Tinio and his men proceeded to Pangasinan to assist Gen. Makabulos in the siege of Dagupan which was the most important of the three Spanish strongholds in the North at that time, the others being Tarlac, Tarlac and San Fernando, La Union. Dagupan was held by the Spaniards under the command of Col. Federico J. Ceballos. In Dagupan, Gen. Tinio met the force of Lt. Col. Casimiro Tinio, composed of Captains Feliciano Ramoso and Pascual Tinio, Lt. Severo Ortega, several other officers, and 300 Novo-Ecijano soldiers. Gen. Makabulos, who had taken over the Central Luzon Command the previous April, was optimistic that he had the situation well in hand and allowed Gen. Tinio and the combined Novo-Ecijano troops at Dagupan to proceed northward to liberate Ilocos from the Spaniards. This Ilocos Expeditionary Force would become the nucleus of the future Tinio Brigade.

The Novo-Ecijano troops, now over 600 strong, reached San Fernando, on July 22, the day that Dagupan surrendered to Gen. Makabulos. They found the capital of La Union already besieged by revolutionists under the command of Gen. Mauro Ortiz. The Spaniards, under the command of Col. Jose Garcia Herrero, were entrenched in the convent, the Casa Tribunal and the provincial jail and were waiting for succour. Gen. Tinio wanted a ceasefire and sent for Col. Ceballos in Dagupan to mediate a peaceful capitulation of the San Fernando garrison. But despite news that the Spaniards had already surrendered Central Luzon to the Revolutionists and the pleadings of Col. Ceballos, the besieged Spaniards refused to capitulate. On the morning of the eighth day, July 31, Gen. Tinio ordered the assault of the convent from the adjoining church. At a cost of 5 lives and 3 wounded, Capt. Alejandrino’s company occupied the kitchen and cut the water supply in the aljibe or cistern under the azotea, the terrace beside the kitchen. At 4 p.m. a 4″-cannon taken from the gunboat “Callao” moored in the harbor was fired against the left side of the convent. The deafening blast frightened the Spaniards who immediately called for a ceasefire and flew the white flag. Alejandrino received the saber of Lt. Col. Herrero as a token of surrender. 400 men, 8 officers, 377 rifles, 3 cannons and P 12,000 in government silver were turned over. Upon seeing his captors, the Spanish commander wept in rage and humiliation, for many of the Filipino officers and men were but mere youths. Gen. Tinio himself had just turned 21 the previous month!

From San Fernando the Tinio Brigade and its prisoners marched on to Balaoan, where they met stubborn resistance from the enemy who were again entrenched in the convent. The siege lasted for five days, and, despite the support of the populace, resulted in the deaths of more than 70 Filipinos, mostly townspeople. Camilo Osías, a witness to the event, wrote in his memoirs that after the siege, the Balaoan katipuneros were inducted en masse into the ranks of the Tinio Brigade. Meanwhile, the company of Capt. Alejandrino, dispatched earlier by Gen. Tinio to reconnoiter and clear the neighboring commandancia or military district of Benguet, had met no opposition for the small force of cazadores in La Trinidad had fled to Bontoc upon learning of their approach. Alejandrino immediately turned back and rejoined Gen. Tinio.

From Balaoan, the rebels marched on to Bangar, the northernmost town of La Union, where they laid siege to the Spaniards holed up, again, in the convent. They won a victory on Aug. 7 after four days of fighting at a cost of 2 casualties. 87 Spaniards surrendered in Bangar.

The Tinio Brigade then crossed the mighty Amburayan River that divides the province of La Union from Ilocos Sur. The colonial force occupying the strategic heights on the opposite bank was the last obstacle to Tinio’s advance to Vigan. Tinio stormed their positions, causing the enemy to withdraw to Tagudin,[5]:250 the first town of Ilocos Sur. There, the Spaniards consolidated all the available forces they could muster (1,500 men according to one source)[5]:250 and prepared to make a stand in the convent and surrounding buildings. However, their spirited defense the first three days turned into a rout, when the native volunteers in the Spanish army deserted their units to fight with the rebels. The Brigade suffered no casualties in that siege. The Spaniards fled north, but were intercepted in Sta. Lucia, Ilocos Sur by Ilocano and Abra revolutionists under Gen. Isabelo Abaya.

The Tinio Brigade, now over 2,000 strong, marched northward and encountered the Ilocano patriots in Sabuanan, Sta. Lucia. The latter escorted them to Candon, whose inhabitants jubilantly received the conquerors.

There, Isabelo Abaya, a native of the place and the initiator of the revolution in Ilocos, was given a regular rank of Captain of Infantry in the Tinio Brigade.

On August 13, 1898, the same day that the Spaniards surrendered Intramuros to the Americans, Gen. Tinio entered Vigan, the capital of Ilocos Sur and the citadel of Spanish power in the North.[5]:251 He found the capital already in rebel hands. Gov. Enrique Polo de Lara, newly appointed Spanish governor of both Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur, had fled to Laoag, the capital of Ilocos Norte, with all the resident Spaniards of Vigan. There he spent five days at the beach of Diriqui, loading the civilians and friars, including Bishop Campomanes, on boats which would hazard the rough weather for the journey to Aparri. He then ordered the troops under Col. Mariano Arques, district commander of the Civil Guards and Jefe de Linea in Ilocos, to take the coastal road to Aparri, Cagayan.

Upon his arrival in Vigan, Gen. Tinio had immediately launched a two-pronged movement to capture the Spaniards fleeing northward and those escaping into the interior.[5]:251 He dispatched his brother, Casimiro, with a light cavalry column of 600 men to Ilocos Norte to pursue the fleeing enemy. Without encountering any opposition along the way, the Filipino column reached Laoag on August 17. They overtook some of the fleeing Spaniards at Bacarra, the next town, where, after exchanging a few token shots, more than 300 Spaniards surrendered. The Spaniards had heard of the humane treatment Gen. Tinio afforded prisoners and did not put up much of a fight.

Two companies were then dispatched to Bangui, the northernmost town of Ilocos Norte, and to Claveria, the first town in Cagayan. Capt. Vicente Salazar’s company pressed the northward pursuit with more tenacity, overtaking the enemy on the road to the Patapat Pass leading to Cagayan province. Right there and then, on August 22, Col. Arques and some 200 Spanish regulars, all tired and frustrated, surrendered almost willingly. In Patapat itself, the crack Regiment No. 70, composed of Ilocano and Visayan volunteers, stationed there to guard the pass, deserted their officers and joined the revolutionaries. The enemy was on the run, and even Aparri at the very end of Luzon was secured too by the detachment under the command of Col. Daniel Tirona.

Relentlessly, from Vigan, Capt. Alejandrino and 500 men, with Capt. Isabelo Abaya as guide, went to Bangued, Abra to track and capture the enemy who were retreating towards the rugged and mountainous interior towns of Cervantes, Lepanto and Bontoc. The Filipinos easily achieved their goal with only 3 casualties, the whole Ilocos and the Cordillera commandancias were now in Philippine hands.

Gen. Tinio is credited with capturing the most number of Spanish prisoners during the revolution, over 1.000 of them. The prisoners were brought to Vigan, their number later augmented by other prisoners sent over from the Cagayan Valley and Central Luzon during the last quarter of 1898. Gen. Tinio exercised both firmness and compassion in dealing with the prisoners. Fray Ulpiano Herrero y Sampedro, a Dominican who had been captured and sent over from Cavite, kept a journal of his 18-month imprisonment together with over a hundred other friars. He wrote that when they were imprisoned in Vigan, “Gen. Tinio wanted to improve the living conditions of the friar prisoners … sent us food, clothing, books, paper and writing implements.”

There was another group of prisoners. The revolucionarios’ anger against the friars extended even to their native mistresses, and these women were imprisoned in the girls’ school beside the Bishop’s Palace. Their properties were confiscated. One of the incarcerated women, a native of Sinait, had a 15-year-old daughter, Laureana Quijano, who pleaded with Gen. Tinio for her mother’s release and the restoration of their properties. The general, attracted to her beauty, forthwith acceded to her request, and then began to court her. Later, Laur, as she was called, also pleaded for the release of another prisoner, her mother’s first cousin, and introduced the daughter, Amelia Imperial Dancel. Again, the general gave in and released Amelia’s mother. Subsequently, Gen. Tinio also fell in love with Amelia.

Gen. Tinio set up his Command Headquarters in the Bishop’s Palace in Vigan. There he lived with 18 of his officers, all very young, mostly 16–20 years of age, the oldest being the 29-year-old Captain Pauil.

In accordance with Aguinaldo’s Dictatorial Decree of June 18, 1898 which set the guidelines for setting up a civil government in those towns liberated from the Spaniards, Gen. Tinio conducted elections for the whole region. First to be elected were the officials of each town. Under the revolutionary government, the mayor, instead of being called the capitan municipal, was now addressed as the presidente municipal. These mayors then elected the Provincial Governor and Board.

With the civil government in place, Gen. Tinio then reorganized the Tinio Brigade. The successful military exploits of the Brigada Tinio were heralded all over Luzon and attracted hundreds of volunteers. The Brigade swelled to over 3,400 men, with scores of officers and more than 1,000 non-commissioned officers and soldiers coming from Nueva Ecija. The rest consisted mostly of Ilocanos, Abreños, Igorots and Itnegs, with a few Bulakeños, Bicolanos and Visayans. There were also some Spaniards in the group.

The Brigade garrisoned the entire western portion of Northern Luzon which included the four genuine Ilocano provinces of Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, Abra and La Union, and also the comandancias of Amburayan, Lepanto-Bontoc and Benguet. Gen. Tinio divided this territory into 3 zones, each under a military commander who commanded a regiment, as follows:

Zone 1 under Lt. Col. Casimiro Tinio covered La Union, Benguet and Amburayan;

Zone 2 under Lt. Col. Blas Villamor covered Southern Ilocos Sur from Tagudin to Bantay, Abra and Lepanto-Bontoc;

Zone 3 under Lt. Col. Irineo de Guzman covered Northern Ilocos Sur from Sto. Domingo to Sinait and Ilocos Norte.

Captains Vicente Salazar, Jose Tombo and Juan Villamor were the deputy commanders.

The establishment of the civil and military government in the Ilocos brought 15 months of peace in the region. The young general and his officers became social denizens sought after and regally entertained by the people. Being young, they caught the eyes of pretty señoritas of the best families in the region. The dashing Manuel Tinio, rich, handsome and a bachelor to boot, seized the moment with the many belles of Ilocandia. He was unforgettably charming and popular. In the 1950s, women reminiscing about their youth, and the Tinios, would look up and sigh, “how handsome they were.” A grandmother from Ilocos Norte living in Baguio City could still passionately say in the 1960s, “all the ladies in the province were in love with the general.” An old maid in Vigan proudly recalled in her twilight years of the 1970s the dashing general’s visits every Friday afternoon when she was 14.

With the Ilocos in stable condition, Gen. Tinio then went to Malolos to report to Gen. Aguinaldo and upon the request of Felipe Buencamino, Minister of Finance, turned over P120,000 that had been contributed by the citizens of Vigan. During his visit, everyone, particularly his fellow generals, admired and congratulated Gen. Tinio for having the largest and best-equipped army in the country!

In October 1898 Gen. Tinio received his appointment as Military Governor of the Ilocos provinces and Commanding General of all Filipino forces in Northern Luzon. His army was formally integrated as an armed unit of the Republic. Thus he became one of only four regional commanders in the Republican Army!

Upon his return to Vigan, Gen. Tinio marshalled his troops, all well equipped and completely in uniform. He assembled them in the town’s main Plaza and made them swear to defend the new Republic with their lives. The next month, on Nov. 11, 1898 Manuel Tinio was appointed Brigadier General of Infantry.

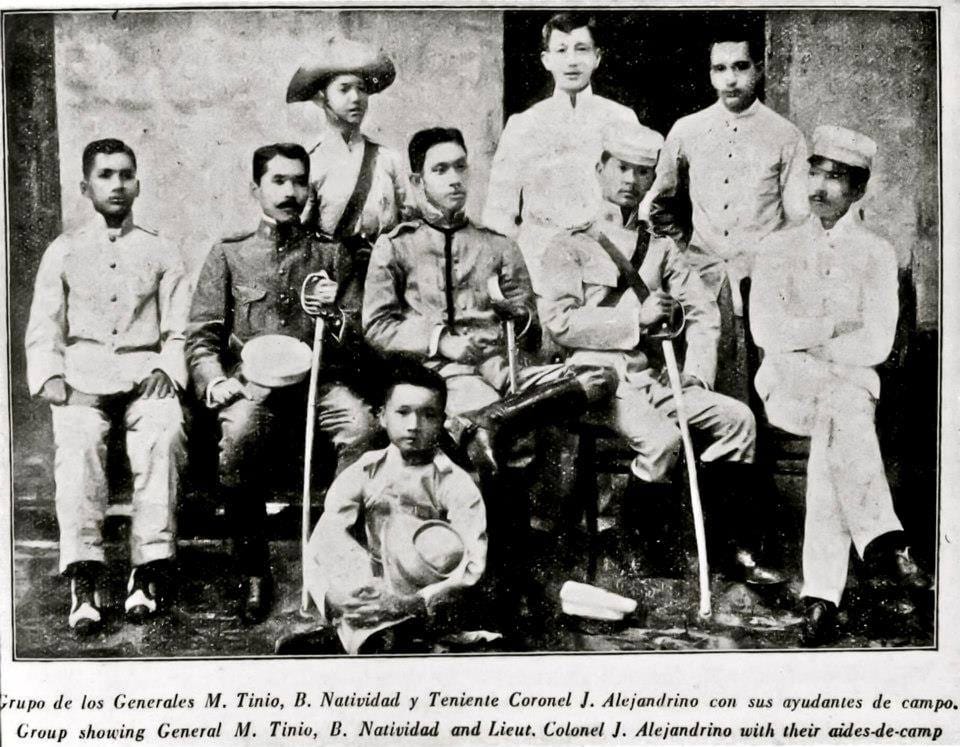

Group showing General Manuel Tinio (seated, center), General Benito Natividad (seated, 2nd from right), Lt. Col. Jose Alejandrino (seated, 2nd from left), and their aides-de-camp.

A shot fired at a Filipino in Sociego Street, Sta. Mesa District in the suburbs of Manila on February 4, 1899 triggered the Philippine–American War. (Contrary to popular belief that prevailed for over a century, the first shot of the Philippine–American War was not fired on San Juan bridge but on Sociego Street in Santa Mesa district, Manila. The Philippines’ National Historical Institute (NHI) recognized this fact through Board Resolution 7 Series of 2003. On Feb. 4, 2004 the marker on the bridge was removed and transferred to a site at the corner of Sociego and Silencio streets.) Soon after, when war with the Americans seemed imminent, Col. Casimiro Tinio and most of the Tagalog troops in the Tinio Brigade were sent back to Nueva Ecija. When the conflict became critical in Central Luzon, all the soldiers in the Brigade who had seen service in the Spanish army were ordered to report to the Luna Division.

The inactivity of the Tinio Brigade during the period of peace in the Ilocos region spawned problems. Boredom led to in-fighting among the soldiers and the perpetration of some abuses. Gen. Tinio adhered to his principles of discipline among his troops, even imprisoning Col. Estanislao de los Reyes, his personal aide-de-camp, who had slapped a fellow officer in an effort to rectify the situation, Tinio asked Gen. Aguinaldo for the assignment of his forces to the frontlines of the new battle at hand, but Aguinaldo paid no heed to Tinio’s request.

Ever keen in foresight and strategy, anticipating an invasion by the American aggressors, Gen. Tinio ordered the construction of 636 trenches, well designed and strategically placed for cross fire, to protect the principal roads and ports and to guard the entire coastline from Rosario, La Union to Cape Bojeador in Ilocos Norte.

At the start of the Philippine–American War, Gen. Tinio’s forces were 1,904 strong, with 68 officers, 200 sandatahanes or bolomen, 284 armorers, 37 medics, 22 telegraphers, 80 cavalrymen, 105 artillerymen and 2 Spanish engineers. (By April 1899, this would be reduced to 1,789 officers and men.)

On May 18, 1899, six months before his forces began battling the American invaders, he married Laureana Quijano.

On June 5, 1899 members of the Kawit Battalion assassinated Gen. Antonio Luna, the commanding general of the republican army. His death in Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija created a lot of antipathy against the Tagalogs, particularly in Ilocos Norte, where Luna hailed from. The Luna assassination, however, did not diminish the love and admiration of the Ilocanos for Gen. Tinio, who referred to the former as ‘my Ilocanos’. Luna’s death resulted in a cooling off in Tinio’s attitude towards Aguinaldo. Tinio, however, never failed to obey the orders of his superior and never made a comment on the deaths of Bonifacio or Luna. Whenever he was asked, he would shrug his shoulders and say, “answering the question would mean a betrayal of my superior.”

Less than two weeks later, on the occasion of his 22nd birthday, delegations from the entire region congregated in the capital to give him an asalto or dawn serenade in the main plaza of Vigan. One of the highlights of the day-long festivities, which included a royal feast and a grand ball, was the dedication of a birthday hymn specially written for him, set to music and sung by the populace.

Towards the end of June, Aguinaldo recalled Gen. Tinio by telegram and ordered him to help in the reorganization of the forces in Nueva Ecija. In his place, Brigadier Gen. Benito Natividad, recently promoted (at age 24) and on leave because of wounds sustained in the Battle of Calumpit, Bulacan, took over as temporary commander of the Ilocos provinces.

Gen. Tinio, seeing the handwriting on the wall, began taking private English lessons from David Arnold, an American captive who had come over to the Filipino side. In anticipation of the coming of the Americans, he began the construction of a formidable bank of defenses in Tangadan Pass between Narvacan, Ilocos Sur and Bangued, Abra.

Late in September, Gen. Tinio and his northern army were finally called to the front line to guard the beaches of Pangasinan and La Union. The Brigade was diminished in size when Gen. Tinio marched with his general staff and several battalions to Bayambang, Pangasinan to cover President Aguinaldo’s retreat while the others were sent to Zambales under Col. Alejandrino.

Gen. Benito Natividad stayed behind as post commander in Vigan with some officers and 50 riflemen, 20 others in Bangued and a few others scattered in neighboring towns. They were the only armed forces that guarded the whole Ilocos region! At that time, there were 4,000 Spanish prisoners of war (including 1 general) and 26 Americans being held in Vigan, Bangued and Laoag, where the military hospitals were located. More than half of the prisoners had been sent from Central Luzon at the height of the hostilities. Despite their great number, the prisoners did not rise up against their guards, because, on instructions of Gen. Tinio, they were well fed and nicely treated. As early as June, American prisoners had begun arriving from the battlefields of Central Luzon. Among them were Navy Lt. Gillmore and the war correspondent Albert Sonnichsen.[5]:382–383 Gen. Tinio’s humane treatment of prisoners was legendary. Sonnichsen wrote:

“. . while in Vigan, Tinio learned that the captive friars were living well on money sent from Manila, while the poor Cazadores were obliged to subsist on their meager rations (as prisoners of war). Before they could hide it, the young Tagalog had their money seized and, having all the soldier prisoners assembled in the plaza, he divided the pesos of the friars equally among them, the Cazadores cheering the Tagalog General lustily.”[5]:252

Having abandoned his last capital in Tarlac, Tarlac, Pres. Aguinaldo decided to retreat to the north and went to Bayambang, Pangasinan. Unknown to him, the Americans had planned a pincer-like movement in the overall battle plan to cut off his northward escape route and capture him.

On November 7, the Americans bombarded San Fabian, Pangasinan and the 33rd Infantry landed, including a battalion commanded by Col. Luther R. Hare, an old cavalryman who had served 25 years before under Gen. Custer.[6]:138 But on Nov. 11, on their way to San Jacinto, the next town, the invaders came across the entrenched forces of Gen. Tinio. Maj. John Alexander Logan, Jr and 8 American soldiers died in the fierce 3.5-hour battle that ensued, but the Americans, armed with a Gatling gun, claimed the lives of 134 Filipino soldiers, wounding 160 more.[6]:144–146

On November 13 a national council of war held in Bayambang resolved to disband the Philippine Army and ordered the generals and their men to return to their own provinces and organize the people for general resistance by means of guerrilla warfare.[6]:146 Gen. Aguinaldo divided the country into zones, each under a general. Gen. Tinio was designated regional commander of the Ilocos provinces. The following evening, Gen. Aguinaldo, accompanied by his family, the cabinet, their aides and the Kawit Battalion, left Bayambang by special train for Calasiao, only 15 kilometers away from American Headquarters!

On November 14, early in the morning, the presidential party struggled through the knee-deep mud of backwoods trails towards Sta. Barbara, where they met with the Mixto Battalion under Lt. Jose Joven and the Del Pilar Brigade. The column, now with 1,200 armed men, managed to reach the forests of Manaoag and proceeded to Pozorrubio, where the party was greeted by Gen. Tinio. The evening before, Maj. Samuel M. Swiggert’s pursuing squadron had caught up with part of the Tinio Brigade in Manaoag, but on the morning of the 14th, failed to pursue Aguinaldo at Pozorrubio.[6]:147

Aguinaldo spent the night in Pozorrubio and was unaware of the proximity of the enemy. He only came to know about it when Gen. Tinio informed him that the Americans were in pursuit. The presidential party hurriedly left for Rosario, La Union, and then for Bauang. Fortunately, the encounters with the Tinio Brigade had delayed the American pincer movements and, by the time these closed, Aguinaldo was already far in the north.

On Nov. 18, 1899 Gen. Samuel B. M. Young with 80 men of the 3rd Cavalry plus 300 native scouts, made a forced march north through Pangasinan in pursuit of Aguinaldo.[6]:151 Ahead of them was Gen. Tinio, who caught up with Gen. Aguinaldo in Bauang, La Union on the 19th. The following day Gen. Tinio, upon Aguinaldo’s orders, accompanied Col. Simeon Villa to San Fernando, La Union, where most of Tinio’s troops were helping the townspeople with the rice harvest. Young’s troops made a surprise raid on the town at 3 in the morning, and, recognizing Tinio and Villa, pursued them. Luckily the two were able to flee into the mountains on foot and to make their way to San Juan, the next town. Gen. Tinio reassembled his men in San Juan and, in an orderly manner, marched with their wounded to Narvacan, only a day or two ahead of the pursuing Gen. Young. Tinio then set up his command headquarters in San Quintin, Abra and sent the wounded further ahead to the military hospital in Bangued.

On Nov. 26, 1899, Vigan became the hottest spot as the American battleship ‘Oregon’ and the former Spanish gunboats ‘Callao’ and ‘Samar’ anchored off it and started shelling Caoayan, Ilocos Sur.[6]:131 Vigan was immediately evacuated on orders of post commander Gen. Benito Natividad. The prisoners, both Spanish and American, together with his meager troops moved on to Abra and Bangued as early as Sept.[6]:120 When the Americans landed the following day, led by Commander McCracken and Lt. Col. James Parker, there were no Filipino soldiers in Vigan.[5]:358 A few days later, 225 American troops, mostly Texas volunteers forming a battalion of the 33rd Infantry under Major Peyton C. March,[6]:153 arrived from San Fabian, took up residence in the Archbishop’s Palace and stored their ammunition and supplies in the adjoining girls’ school.

On Nov. 27, the day the Americans occupied Vigan, Gen. Tinio sent orders for all active soldiers of the Brigade to concentrate along the shores of the Abra River towns of San Quintin, Piddigan and Bangued, beyond the Tangadan Pass. Gen. Young, who was chasing them relentlessly; had reached Candon on the 28th and, from seized documents, discovered that he was no longer trailing the enemy, but was right in their midst! He also learned that Aguinaldo was at Angaki, 25 km. away to the southeast, while Tinio was up north some 40 km. away.[6]:153 Young realized immediately that Gen. Tinio’s purpose in taking his forces to the north was, as he phrased it, “to lead us away from following Aguinaldo.” Unsure whether he should pursue Aguinaldo or go after Tinio, the decision was made for him when a battalion of the 34th Volunteer Infantry arrived under Lt. Col. Robert Howze. They had been sent by Gen. Arthur MacArthur to reinforce Gen. Young’s northern column.[6]:154 Forthwith, March’s battalion was sent in pursuit of Aguinaldo through Tirad Pass, while the bigger part of Young’s army, with Howze’s battalion, marched towards Tangadan Pass in an attempt to destroy the Tinio Battalion, the last remaining army of the Republic.[6]:156

From San Quentin, General Tinio ordered 400 riflemen and bolomen, led by Capt. Alejandrino, went down the Mestizo River in bancas and spread out on both sides of the plaza of Vigan.[6]:163 Just before 4 AM on 4 Dec., some of the attackers in the dark streets were challenged by an American patrol who then gave the alarm to the 250 Americans in the city.[6]:163 Although Filipino snipers were already in position in the buildings around the plaza, in the ensuing 4-hour battle at close range they were no match for the legendary Texas marksmanship and the inexhaustible supply of American ammunition. The rebels were routed, leaving over 40 dead and 32 captured, while 8 Americans were killed.[6]:165 The survivors fled to Tangadan.

By 3 Dec. 1899, Gen. Young and Lt. Col. Howze were at Tangadan Pass with his 260 men.[6]:165 The pass was defended by 1,060 men under Lt. Col. Blas Villamor, Tinio’s chielf of staff, in trench works constructed over the last year with the assistance of Spanish engineers.[6]:162 The Americans successfully scaled the steep, 200-foot cliffs flanking the entrenchments to gain a vantage position.[6]:168–169 The final assault came in the evening of Dec. 4, added by the arrival of Col. Luther Hare’s 270 men from the 33rd Infantry.[6]:168–169 Outflanked and outnumbered, Lt. Col. Villamor decided to save his men from carnage, and retreated, abandoning rifles and ammunition, and after losing 35 killed and 80 wounded to the American loss of 2 killed and 13 wounded.[6]:170Thus ended the Battle of Tangadan Pass.

Tinio, however, earned the admiration of Col. Howze who wrote glowingly on the Vauban-type Tangadan defenses:

“The trenches captured are the best field trenches that have ever come under my observation. They terrace the mountainside, cover the valley below in all directions, and thoroughly control the road for a distance of 3 miles. They are permanent in nature, with perfect approaches, bomb-proofs, living sheds, etc., with shapes and revetments sodded and supported by timbers. The complete terrace of trenches number 10 in all, well connected for support, defense and retreat.”

Gen. Young reported on the bravery of General Tinio and his men, that at the Battle of Tangadan,

“Some of their officers exposed themselves very gallantly on the parapets during heavy firing.”

The day after the Battle of Tangadan, December 5, the pursuing Americans invaded Tinio’s headquarters in San Quintin, five kilometers away from the pass.[6]:171 They continued upstream on the Abra River to Pidigan and Bangued, liberating 1,500 starving Spaniards, on 6 Dec.[6]:171, 173 The American prisoners and the Spanish general had been sent ahead to Ilocos Norte by Gen. Tinio for strategic reasons, with orders for them to be shot rather than be rescued by the Americans.[6]:172 But the capture of Bangued was a major setback for the Filipinos, because the Brigade arsenal was located there. Three tons of sheet brass, two tons of lead, as well as supplies of powder, saltpeter and sulphur were found by the Americans. General Benito Natvidad joined General Tinio at Tayum.[6]:193

The onslaught had started! Having captured Bangued, Gen. Young re-armed at Vigan and within a week made unopposed landings in Ilocos Norte at Pasuquin, Laoag and Bangui. He sent cavalry north from Vigan, destroying trenches and defense works around Magsingal, Sinait, Cabugao and Badoc.

Meanwhile, the rescue of the American prisoners from Bangued became the task of Col. Hare’s 220 men of the 33rd Infantry and Col. Howze’s 130 men of the 34th Infantry.[6]:172

In Abra, Gen. Tub had been roaming the farms disguised as a rich planter on a white horse. In this way he made regular daily visits to the various American outposts to chat with the enemy soldiers. He even went so far as to invite them to his house in Bangued for dinner. After gathering all the information that he could, Tinio went back to the hills each day to instruct his men on what to do that night. Unfortunately, one day his photograph was circulated among the Americans and the daring general had no choice but to take to the hills with Col. Hare and a picked group trailing him!

Howze caught up with the Brigade’s baggage train in Danglas on 8 Dec.[6]:182 and 750 more Spanish prisoners on 10 Dec. at Dingras[6]:188 This last group included General Leopoldo Garcia Pena, former commander of Cavite province.[6]:188 Hare’s column joined Howze at Maananteng, where they sent the freed Spanish and Chinese prisoners on to Laoag, and the remaining force of 151 men continued the pursuit into the Cordilleras on 13 Dec.[6]:189–192

When Gen. Tinio realized that the Americans were exerting all efforts to surround him, he had the American prisoners conducted to Cabugaoan in Apayao country as a diversion, spreading false rumors that he was with the group. (He had, in fact, on Dec. 12, though surrounded by the Americans in Solsona, Ilocos Norte, near the boundary of Apayao, managed to elude them dressed as a peasant woman.)[6]:189

After days of marching in the wild Cordillera Mountains, the Americans finally caught up with the abandoned prisoners on Dec.18 at the headwaters of the Apayao-Abulug River, having been abandoned by their Filipino guards in Isneg territory.[6]:207–208 On crudely constructed rafts, the Americans eventually reached the coast in Abulug, Cagayan, on 2 Jan. 1900, where the footsore and weary soldiers found the USS Princeton and USS Venus waiting to take them back to Vigan and Manila.[6]:217

Gen. Tinio spent the next couple of months in the mountains of Solsona, where he began fortifying the peak of Mt. Bimmauya, east of Lapog. It was also in the remote headwaters of the Bical River above Lapog that an arsenal had been set up to replace that captured at Bangued. This operated for a year. Rifles were repaired, cartridges refilled, gunpowder and homemade hand guns (paltik) manufactured with real feats of mechanical ingenuity. Twenty to thirty silversmiths and laborers could fashion 30-50 cartridges a day by hand!

The defenses constructed by Gen. Tinio were similar to those that he had put up in Tangadan the year before, but, having learned his lesson, he situated the defenses on a peak that Lt. J. C. Castner described as follows:

“one of the principal peaks (is) on the coast range of northwestern Luzon. Its altitude is between 2,500 and 3,000 feet above the Rio Cabugao that washes its western shore. By reason of standing more to the westward than its immediate neighbors and being bare of timber, it affords a view of the entire coastal plain from Vigan on the South to Laoag on the north. The lower part of Monte Bimmauya is wooded, but the upper three-fourths is bare of trees and bush, and, in certain places, even the grass has been burned off by the insurgents. Consequently, there is no cover for attacking troops ascending the western spur of the mountain. The slopes of the upper portion make angles of from 45-60 degrees with the horizon. The only trail in existence or even possible on this western spur… is so narrow that it is what is known among geographers as a ‘knife-edge’, hence the only formation admissible was a column of files, two men not being able to march abreast. The ascent is so steep and the footing so insecure that one has to watch continually where he plants his feet to avoid precipitation down the precipice-like slopes on either side.”

New Year’s Day 1900 signaled the outburst of guerilla warfare throughout the Ilocos region. On that day, Gen. Tinio engaged in a skirmish with American forces at Malabita, San Fernando, La Union. The disconcerted Gen. Young ordered daily patrols by all his units “to settle this insurgent business with the least possible delay.” The following day, he requested another battalion of veterans with which he promised “to drive these outlaws out or kill them and settle the savages before letting up.” The day after that he repeated the request:

“My belief is that by keeping up a constant hunt after these murderers, thieves and robbers, the country can be cleared of them within two months.” Needless to say, he did not receive any reinforcements, because he already had 3,500 men, more than thrice the number of Tinio’s troops!

On January 13 the Americans intercepted an order from Gen. Tinio to execute all Filipinos who surrender to the enemy.

The following day, January 14. the only artillery duel of the Fil-American War was fought in Bimmuaya between the Republicans and the combined forces of Maj. Steever and Lt. Col. Howze. The barrage lasted from noon until sundown. Despite holding the ‘strongest position in Luzon’, as Steever believed the Bimmuaya stronghold to be, the Filipinos, with their paltry stock of rifles and ammunition, succumbed in less than 24 hours to the mighty American forces. Steever’s two Maxim guns dominated the show. Although the Americans halted their fire at sunset, the Filipinos kept up desultory fire until midnight. The next day the Americans discovered that it was just to cover the withdrawal of Gen. Tinio and his men!

After the Battle of Bimmuaya, Gen. Tinio’s guerrilla forces continuously fought and harassed the American garrisons in the different towns of Ilocos for almost 1½ years. His command was probably the first to initiate guerrilla activities in Luzon in accordance with the Aguinaldo’s official proclamation at Bayambang on Nov. 12, 1899. Once again, he reorganized the Tinio Brigade, now greatly reduced by the casualties sustained in San Jacinto, Manaoag and other places. Discarding its inter-provincial designation of units, he reformed his forces as a guerrilla organization with overlapping territories and troops, Ilocos Sur being shared by other Ilocano provinces. The military commands came to be known as:

· Ilocos Norte-Vigan Line covering the province of Ilocos Norte south to northern Ilocos Sur down to Vigan, · Abra-Candon Line under Lt.-Col. Juan Villamor which covered the Province of Abra and Ilocos Sur south of Vigan down to Candon · La Union-Sta. Cruz Line covering the province of La Union north to southern Ilocos Sur as far as Sta. Cruz.

The battalion commanders came to be known as Jefes de Linea, while the company commanders were now called Jefes de Guerrilla. Companies of riflemen became numbered units of guerrillas, each ranging from 50-100 soldiers, depending on the number of fighters a unit could arm and equip. These troops were then divided further into destacamentos or detachments of 20 men, more or less, under a subaltern officer. These bands were virtually independent of each other in their operations. But they could function occasionally as a unit on rare instances of mass assaults, as in the raids on Laoag on April, Bangued in June and Candon in February 1901.

Col. Bias Villamor, now 2nd in command as a result of his good showing in the Pangasinan campaigns, gave the full count of the Tinio Brigade in January 1900 at 1,062 men, 64 of them officers. The high proportion of officers to men was due to the nature of guerrilla warfare with its small separate units and flying columns of 20-30 men that strike at their chosen times and places. The majority of the officers were Novo-Ecijanos and veterans of earlier campaigns, some even from the Revolution of 1896!

The use of guerrilla tactics by the Filipinos resulted in more American losses than they had previous to Nov. 14, 1899. The never-ending guerrilla raids forced Gen. Young to start garrisoning the towns, setting up 15 of them in January, 4 in March and a total of 36 by April. Detachments varied in size from 50 in San Quintin, 200 in Sinait to 1,000 in Cabugao and Candon. These garrison troops were under fire in one place or another for the next 18 months. Cabugao alone was attacked every Sunday for 7 consecutive weeks! Ambuscades of American patrols became almost a daily occurrence and resulted in so many casualties for the invaders, that by March 1900, no patrols were sent out unless they were 40-50 strong! Gen. Arthur MacArthur, in an official report, stated that:

“The extensive distribution of troops has strained the soldiers of the army to the full limit of endurance. Each little command has had to provide its own service of security and information by never ceasing patrols, explorations, escorts, outposts and regular guards. . . In all things requiring endurance, fortitude and patient diligence, the guerilla period has been pre-eminent.”

The “secret weapon” of these attacks was the Ilocano people. The whole population was an espionage network and developed a warning system to apprise the revolutionists of approaching invaders. Even priests would tap church bells as a warning of approaching American patrols. Pvt. James Lyons, a prisoner in Tinio’s camp, reported that “runners came in every few minutes” with information. It seemed that the whole Ilocos was now engaged in war, with trade and agriculture virtually at a standstill!

Gen. Tinio’s raids were so sporadic and simultaneous that many, including the Americans, believed that Tinio had the power of bilocation, appearing in several places at the same time! His personal movements indicated an energetic contact with his forces – organizing, inspecting, consulting, encouraging or commanding in action, and constantly eluding his would-be captors. He was everywhere.

On 31 January, Gen. Tinio and his men had a skirmish on the Candon-Salcedo road with American troops. Fortunately they did not suffer any casualties.

The next day, February 1, Tinio, visited Sto. Domingo, unescorted and dressed as a farmer.

On February 9, he ambushed a troop of 7 cavalry in Sabang, Bacnotan, but withdrew when American reinforcements arrived.

On 16 February, from Bacnotan, he ordered Capt. Galicano Calvo to apprehend certain American spies.

On February 19, he ambushed an enemy patrol in Kaguman and captured the equipment.

On February 26, he ambushed an American convoy between San Juan and Bacnotan, together with their supplies of food, medicine, shoes, mules, etc.

On March 5 the next month, he surprised and routed an American camp in San Francisco, Balaoan, capturing all the equipment. He then went north to Magsingal, but left the next day on an inspection trip.

On the 8th, a surprise search for him in Sto. Domingo and San Ildefonso was frustrated by warnings of church bells.

On the 10th, he issued a warning to the Mayor of Candon, prompting the American command there to request for a picture of Gen. Tinio.

On the 14th, while holding a meeting in Bacnotan, he was surprised by an American patrol. Fortunately, a troop of Filipino cavalry arrived, and, with the support of two guns in the house, the Filipinos were able to repulse the attackers and enable Tinio to escape.

Two days after, on the 16th, Tinio met with Mayor Almeida in Bacsayan, Bacnotan.

On March 29, Gen. Tinio and his escort had a skirmish with an American patrol and routed them. An escaping American was drowned in the river between San Esteban and Sta. Maria.

In April, Tinio reported to Aguinaldo in Lubuagan, Kalinga and in May conferred with Aglipay in Badoc and fought a battle in Quiom, Batac, Ilocos Norte. He then moved on to Piddig, Ilocos Norte and, in June he set up a camp at a remote peak called Paguined on the Badoc River east of Sinait. The last was near his arsenal in Barbar.

All this incessant movement did not detract from his love life. Although he was already married, he continued his various liaisons, even going to the extent of bringing Amelia Dancel into the mountains of Ilocos Norte with him in July. American military reports even mention Amelia as his wife! In disguise, he once visited a maiden in enemy-occupied Vigan. The Americans, hearing that he was in town, began to make a house-to-house search, but were unable to find him, even when they searched his ladyfriend’s house. The woman had hidden him under the voluminous layers of her Maria Clara skirt! That was probably the narrowest escape he ever made! The incident became the talk of the town and was always cited whenever the name of Gen. Tinio came up. (The quick-thinking “heroine” lived until the 1970s.)

By November 1900, the number of American forces in the Ilocos had increased to 5,700 men—plus 300 mercenaries. The number of garrisons also rose to 59, spread thinly over 250 kilometers from Aringay, La Union to Cape Bojeador, Ilocos Norte. Earlier, mercenaries had been brought in from Macabebe, Pampanga and were stationed in Vigan, Sta. Maria, and San Esteban. These mercenaries started recruiting fellow Filipinos and by April numbered over 200, half of them Ilocanos and a quarter of them Tagalogs. Attached to regular occupation troops, these mercenaries caused significant damage to the nationalists by leading the enemy to hidden food supplies and inducing many defections. Because of this, Gen. Tinio issued a proclamation on March 20, 1900 as follows:

First and last article. The following shall be tried by summary court martial and sentenced to death:

- All local presidents and other civil authorities, both of towns and of the barrios, rancherias (settlements of Christianized tribesmen) and sitios or hamlets, of their respective jurisdictions, who do not give immediate notice of any plan, direction, movement or number of the enemy as soon as they learn of it.

- Those who, regardless of age or sex, reveal the location of the camp, stopping places, movements or direction of the revolutionaries to the enemy.

- Those who voluntarily offer to serve the enemy as guides, unless it be for the purpose of misleading them from the right road, and

- Those who, whether of their own free will or not, capture revolutionary soldiers who are alone, or persuade them to surrender to the enemy.

The insidious guerrilla war saw such rules and warnings proclaimed from both parties. The American commands in Ilocos Norte were ordered to warn barrio officials that those who did not report ‘insurgents’ immediately (meaning, within an hour for every 5 km. from the nearest American troops) would be considered insurgents themselves, and their barrios ‘absolutely destroyed’. Theft of telegraph wires or ambuscades of American patrols resulted in the nearest villages being burned and the inhabitants killed. When 200 m. of telegraph wire was destroyed in Piddigan, Abra, the Bangued command reported the next day that, “There is not a single building standing out of Piddigan.”

Gen. Tinio, on the other hand, ordered all the towns to aid the revolutionaries. Pasuquin, a town in Ilocos Norte, refused to cooperate with Filipino forces, so Tinio threatened to burn the town “at his leisure” and did so on Nov. 3, 1900.

On Dec. 21, Gen. Tinio issued a proclamation against crimes by military forces. On Christmas Day, Tinio, with Maj. Reyes and ten officers celebrated the holiday in Lemerig near Asilang, Lapog. On Holy Innocents’ Day, Dec. 28, the Americans made a surprise raid on Lemerig. Fortunately, the general and his officers managed to escape.

The first month of 1901 began inauspiciously with the capture of Gen. Tinio’s arsenal at Barbar on January 29, 1901.

The following month, on February 19, 1901, Brigadier Gen. James Franklin Bell came into the picture. Gen. Young turned over the command of the First District, Department of Northern Luzon to him. It is this General Bell who would later gain notoriety for his ‘re-concentration’ methods in the southern Tagalog provinces right after his stint in the North.

Determined to continue the same policy of repression, Gen. Bell, with an additional 1,000 men, ordered his forces to pursue, kill and wipe out the insurrectos. Food supplies were destroyed to prevent them from reaching the guerrillas. Inasmuch as the barrios were supplying rice from the recent harvests to the guerrillas, whole populations were evacuated to town centers within 10 days of notification. Noncompliance resulted in the burning of the whole barrio. Even some interior towns were completely evacuated, while others, like Magsingal and Lapog were surrounded by stockades to prevent the revolutionaries from infesting them.

On February 26, Gen. Tinio attacked the Americans fortified in the convent of Sta. Maria. It was his last attack against American forces.

The whole Ilocos was being laid waste and was in danger of starvation due to Gen. Bell’s iron fisted policies. The lack of supplies eventually forced hundreds of patriots to lay down their arms and return to their homes. By March the Brigade only had a few hundred soldiers left.

On March 25, 1901, the top brass of the Tinio Brigade met in a council of war at Sagap, Bangued. In this meeting, Generals Tinio and Natividad, the two Villamors and Lt. Colonels Alejandrino, Gutierrez and Salazar resolved that “the final action of the Tinio Brigade should depend upon the decision of the Honorable President.”

Unknown to them, Aguinaldo had been captured in Palanan, Isabela on March 23, 1901. When word of Aguinaldo’s surrender reached Gen. Tinio on April 3, he only had two command-rank subordinates remaining, his former classmates Joaquin Alejandrino and Vicente Salazar.

On April 19, 1901 Aguinaldo proclaimed an end to hostilities and urged his generals to surrender and lay down their arms. In compliance with Gen. Aguinaldo’s proclamation, Gen. Tinio sent Col. Salazar to Sinait under a flag of truce to discuss terms of surrender. The following day, Salazar was sent back with the peace terms. On April 29, 1901, Gen. Manuel Tinio, whom the American military historian, William T. Sexton, called “the soul of the insurrection in the Ilocos provinces of Northern Luzon” and “a general of a different stamp from the majority of the insurgent leaders”, surrendered. The following day, April 30, he signed the Oath of Allegiance. When Tinio handed his revolver to Gen. Bell as a token of surrender, the latter immediately returned it to him – a token of great respect. Gen. Tinio was only 23 years old!

The Americans suspended all hostilities on May 1 and printed Tinio’s appeal for peace on the Regimental press on the 5th. On May 9 he surrendered his arms together with Gen. Benito Natividad, thirty-six of his officers and 350 riflemen.

While the Americans boasted that they eliminated 5 insurrecto generals within a month, it took them 11/2 years and 7,000 men to ‘civilize’ Manuel Tinio y Bundoc, the Tagalog boy-general of the Ilocanos!

The significance attached to Gen. Tinio’s surrender by the Americans was felt throughout the country. Gen. MacArthur said that the little war in the Ilocos was the “most troublesome and perplexing military problem in all Luzon.” On May 5, as Military Governor of the Philippines, MacArthur issued General Order No. 89 releasing 1,000 Filipino prisoners of war “to specially signalize the recent surrender of Gen. Manuel Tinio and other prominent military leaders in the provinces of Abra and Ilocos Norte.” La Fraternidad, a Manila newspaper, happily reported, “The 1st of May is now for 2 reasons an important date in contemporary Philippine history – 1898, the destruction of the Spanish squadron in Cavite; 1901, the surrender of Generals Tinio and Natividad and the complete pacification of Northern Luzon.

Manuel Tinio, surprisingly, never suffered any injury during his entire military career even as he was known to stand up and face a barrage of artillery fire! He attributed this to an amulet, anting-anting, that he always wore and which he kept in a safe after the cessation of hostilities.

Upon his release, Manuel Tinio went back to Nueva Ecija to rehabilitate his neglected farms in present-day Licab, Sto. Domingo and Talavera. He lived in a camarin or barn together with all the farming paraphernalia and livestock. A typical hacendero, he was very paternalistic and caring, extending his protection, not only on his family, but also to his friends and supporters. His men even compared him to a ‘hen’.

As a family man, he was very protective of his daughters. Being family-oriented, he took in all the children of his deceased sisters and half sisters (from his father’s previous marriages) when their widowers eventually remarried or played around. He treated all his nephews and nieces as if they were his children, giving them the same education and privileges. This resulted in the extremely close family ties of the Tinio Family. He was very loving and fatherly and would entertain his children with stories of his campaigns. Perhaps because he never finished high school, he believed in a good education and, in 1920, sent his two eldest sons to the United States to study in Cornell University.

Manuel Tinio treated everyone equally, rich and poor alike, so everyone looked up to him and respected him. In fact, he paid more attention to the poor than to the rich, because, according to him, the poor had nothing but their pride and were, for that reason, more sensitive. When rich relatives came to visit, his children had but to kiss their hand in greeting, but when a poor relation came, they had to greet their kin in the same manner, but on bended knees – the highest form of respect in those days!.

All his tenants idolized Manuel Tinio, who was not an absentee landlord, but lived with them in the farm with hardly any amenities. However, he always kept a good table and had flocks of sheep and dovecotes in every property he owned, so that he could have his favorite caldereta and pastel de pichon anytime he wanted. He also enjoyed his brandy, finishing off daily a bottle of Tres Cepes by Domecq. Wherever he lived, he received a constant stream of visitors, relatives and friends. Many veterans of the Tinio Brigade, often coming from the Ilocos, invariably came to reminisce and ask for his assistance. Later, as Governor, he would help them settle in Nueva Ecija.

Although he was but a civilian, the prominence he earned as a revolutionary general and his immense network of social and familial alliances eventually became the nucleus of a political machine that he controlled until his death. An ardent nationalist, he fought against the federalists who wanted the Philippines to become an American state. He did not run for any position, but any candidate he endorsed was sure to win the position. Dr. Benedicto Adorable, one of the richest and most prominent men in Gapan, was so fanatically loyal that he often said, “I would vote for a dog if Gen. Tinio asked me to.” Of course, he was fanatically loyal because Gen. Tinio had saved him from a Spanish firing squad in 1896!

When Gov. Gen. Henry C. Ide lifted the ban on independence parties in 1906, the political parties with similar ideology merged into the present Nacionalista Party. Manuel Tinio always supported Sergio Osmeña, the leader of the party, throughout his political career. Even during the split between Osmeña and Quezon in 1922, Tinio remained loyal to the former. As the founder and leader of the Nacionalista Party in Nueva Ecija, Tinio stressed the significance of a unified party, emphasizing in every local party convention that the winner will be supported wholly by each party member. Any party member who won an election could serve only one term in office to give the other party members a chance. Should the incumbent seek re-election, Tinio advised his colleagues to support the choice of the convention. As a party leader, he did not want warring factions within the party, and exerted every effort to make rival groups come to terms. Thus, during his lifetime, the Nacionalista Party in Nueva Ecija was unified.

On July 15, 1907 Gov. Gen. James F. Smith appointed Manuel Tinio as Governor of the Province of Nueva Ecija, to serve the remainder of the 3-year term of Gov. Isauro Gabaldon, who had resigned to run as a candidate for the 1st National Assembly. Incidentally, one of the first major bills Assemblyman Gabaldon proposed was the establishment of a school in every town in the archipelago. The Gabaldon-type schoolhouses and Gabaldon town in Nueva Ecija are named after him. Gabaldon’s wife, Bernarda, was the eldest daughter of Casimiro Tinio.

Manuel Tinio’s first term as governor was marked by the return of peace and order to the province. William Cameron Forbes, Commissioner of Commerce and Police under both Gov.-Generals Wright and Smith, wrote of Tinio:

“…we picked up the new Governor of Nueva Ecija at San Isidro, the capital, General Tinio. He used to be a celebrated insurecto General and Governor Smith has just made him Governor.. . We have more robbery and murders here than almost anywhere, one leading band being continually on the move. General Tinio informed me that he had most of the band in jail already, his guns captured, and the robberies stopped, and the principal outstanding ladron (the only one that I know by name in the whole of Luzon) driven from his borders and over to Pangasinan. I talked busily on road building and maintenance to him for a couple of hours while we sped up to Cabanatuan and went up to call on the local officials..

An anecdote on Gov. Tinio’s bravery has him negotiating with a dreaded tulisan or bandit who held a family hostage for days, threatening to kill them if the constables, policemen, tried to rush him. Unarmed, Tinio went into the house, talked to the bandit and went out after 30 minutes with the bandit peacefully in tow.

Gov. Tinio also brought about agricultural expansion. His Governor’s report for the fiscal year 1907–1908 stated that the area of cultivated land increased by 15%. The following year, this was augmented by an additional 40%. These lands, which were settled by over 5,000 homesteaders, mostly Ilocanos, were in the towns of Bongabon (then including Rizal), Talavera, Sto. Domingo, Guimba (which still included Muñoz) and San Jose. The influx of settlers from the north explains why many people speak Ilocano in those towns today.

It was also during his term as Governor that his wife, Laureana, died. The Provincial Board then passed a resolution naming the town Laur, after her. Soon after, he married Maura Quijano, the younger sister of Laureana, who had accompanied her from Ilocos after Gen. Tinio’s surrender to the Americans.

Gen. Tinio ran for reelection under the Nacionalista Party in 1908 and won. But there were other things in store for him. His executive ability and decisiveness had not gone unnoticed by the Americans, especially by Forbes who had become Acting Gov. Gen. on May 8, 1909. Months before Forbes assumed the office,

“Manila was being troubled by a series of strikes generally fomented by the shamelessly corrupt labor leader Dominador Gomez, who was taking a cut out of sums levied as blackmail against major American firms. Gomez had been arrested for threats, and some of the other unions collapsed when Gov.-Gen. Smith had questioned the legality of the unions’ use of their funds.”

To help settle labor problems, Forbes set up the Bureau of Labor and asked Manuel Tinio to head it. Forthwith, Tinio resigned as Governor of Nueva Ecija and became the first Director of Labor on July 1, 1909, thereby becoming the first Filipino Bureau Director! He quickly solved the strikes. Three weeks later, Forbes welcomed Director Tinio to his staff meeting and wrote in his diary:

“He’s a good man, and Col. Bandholtz says he’s got Gomez scared to death… Gomez had tried Tinio to employ him, but Tinio refused: “Why pay you to do the work the Government is paying me to do?”

“In a short time the condition of labor and industry in the region about Manila was vastly improved. In general, it may be said that, as a result of Gen. Tinio’s management of the bureau, strikes ceased, laborers went their way contented, employees readily corrected abuses brought to their attention, and the (union) leaders fell back into their proper role of caring for and representing the laborers.”

Manuel Tinio eventually became a close friend of the aristocratic Forbes, whom he invited to hunting parties in Pantabangan. The latter liked Tinio’s company, even offering to give him a hectare of land along Session Road in Baguio, (newly developed by Forbes) so that Tinio could build a house there and keep him company whenever he went up to the cool mountain resort. Tinio did not accept the offer. Gov.-Gen. Forbes also wrote in his journal:

“Tinio later became a great friend of mine. I made him Director of Labor and I rated him as one of the best Filipinos in the Islands. In fact, from the point of view of staunchness of character, and good judgement, and other good qualities, I liked Tinio best of all and wanted to make him Commissioner [member of the Philippine Commission].”

Gov.-Gen. Francis Burton Harrison succeeded Gov. Forbes. His term was characterized by increased Filipinization of the insular bureaucracy, and he appointed Tinio as the first Filipino Director of Lands on October 17, 1913. It was while he was Director of the Bureau of Lands that cadastral surveys for each municipality began to be made, and the area now covered by the towns of Rizal, Llanera, Gen. Natividad, Laur, Lupao and Muñoz were subdivided into homesteads. In the largest wave of migration ever experienced by the province, thousands of landless Tagalogs and Ilocanos came and settled in Nueva Ecija. But Tinio suffered intrigues sown by the American Assistant Director, who wanted to be appointed to the position. The intrigues came to the point that Tinio was even accused of manipulating the sale of the 6,000 hectare Sabani Estate that was subsequently rescinded. In disgust and for delicadeza, he resigned on September 13, 1914 and returned to Nueva Ecija to manage his landholdings. A subsequent investigation cleared him of all charges, but, disillusioned with the government system, he refused to go back to government service, preferring to live the quiet life of a landowner instead. The Sabani Estate, in present-day Gabaldon, Nueva Ecija and Dingalan, Aurora, never found another buyer and still belongs to the government and is administered by the National Development Corporation.

It was during his term as Director of Lands that his wife, Maura, died. He then married Basilia Pilares Huerta, a Bulakeña from Meycauayan.

After his resignation from the Bureau of Lands, Manuel Tinio went back to Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija, and built his house on Burgos St. It was the largest house in town. He entertained and kept open house, which meant that anyone present at lunchtime was automatically invited to dine. Everyday was like an Election Day – with people coming to ask for assistance, financial or otherwise. A very generous man, he was not averse to using his personal financial resources to help those in need.

Manuel Tinio dedicated the remainder of his life to politics. The hold that Manuel Tinio had on the province was awesome. Even if he did not have any position, he maintained absolute control over the local government with the unchallenged power to make or unmake provincial leaders. In order to maintain and gain his political power, Manuel Tinio made it a practice to visit every voter during an election year, reserving for last those who were known to be against his party. A few days before the election, Tinio would visit them. He would sit where everyone who passed by the house could see him. After chatting with his host for an hour or two, without even discussing politics, the whole barrio would conclude that the fellow had been won over by Tinio! His credibility with his partymates shattered, the poor fellow had no choice but to move over eventually to the Nationalista Party!

Lewis Gleeck wrote of Manuel Tinio as “the supreme example of caciquism in the Philippines” and cited the case of one of Tinio’s most prominent political leaders who had shot and killed a man in front of many witnesses. The Americans, wanting to show that there was equality under American law, tried to make a big case out of it. However, they could not find a single lawyer in the whole province willing to act for the prosecution. After sending an American lawyer from Manila, the case had to be dismissed, because no witness came up to testify! J. Ralston Hayden, a high American official, said:

“Tinio controlled the entire government: the Courts of First Instance, the Justices of the Peace, the chiefs of police and police forces, the mayors and the councilors. These, together with a tremendous money power, were in his hands. No one dared to stand up against him.”

Manuel Tinio was also a very good friend of Manuel Quezon and Sergio Osmeña, the Speaker of the National Assembly and the most powerful Filipino in the political scene at that time. It was not surprising, therefore, that Manuel Tinio was included in the Independence Mission that went to Washington D. C. in 1921.