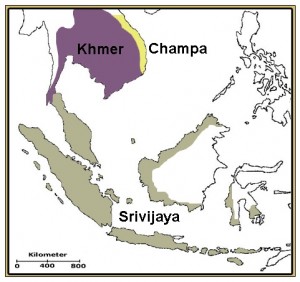

A new translation of the Calatangan Pot inscription The Calatangan Pot is a prehispanic (14th-16th century) artifact containing an inscription around the neck. It is said to be one of the earliest expressions of prehispanic writing in the Philippines, and there have been several attempts at translating the inscription. Rolando Borrinaga is the latest person to offer an translation of the script, based on old Bisayan and old Tagalog alphabets. An earlier attempt to decipher the Calatangan Pot incription was made by University of the Philippines’ Ramon Guillerm *** The mystery of the ancient inscription The Inquirer, 23 May 2009 AFTER 50 years of enigma, the text inscribed around the shoulder of the Calatagan Pot, the country’s oldest cultural artifact with pre-Hispanic writing, may have been deciphered as written in the old Bisayan language. Diggers discovered the pot in an archeological site in Calatagan, Batangas, in 1958. They sold it for P6 to a certain Alfredo Evangelista. Later, the Anthropological Foundation of the Philippines purchased the find and donated it in 1961 to the National Museum, where it is displayed to this day. The pot, measuring 12 centimeters high and 20.2 cm at its widest and weighing 872 grams, is considered one of the Philippines’ most valuable cultural and anthropological artifacts. It has been dated back to the 14th and 16th centuries. *** The Calatagan Pot by Hector Santos © 1996 by Hector Santos All rights reserved. http://www.bibingka.com/dahon/mystery/pot.htm In the early 1960's, an artifact was offered by treasure hunters to National Museum staff as they were working on a nearby excavation. It was the Calatagan pot, the first pre-Hispanic artifact with writing to be found. As such, it is the best known and written about among all artifacts with writing. Even at that, it is still undeciphered. Calatagan Pot The late Dr. Robert Fox brought the pot to the offices of the Manila Times to ask help from its editor, Chino Roces, in deciphering the writing around the mouth of the pot. The newspaper, as a result, commissioned the sculptor Guillermo Tolentino, an expert on Philippine syllabaries, to decipher the writing. Tolentino had a hard time with certain letters so he, as a spiritist, reportedly summoned his special powers to come up with a translation. The authenticity of the pot has been questioned since it first showed up. For one thing, no other pot has been found decorated with writing. Carbon dating was reportedly done on the pot but the results pointed to such an extremely early date that it had to be rejected. Dr. Fox wanted to do some thermoluminescence testing but didn't live to see it done. Nevertheless, the pot may still be authentic. It would have been very easy for a forger to write something decipherable on the pot, especially text which made sense. Anyone attempting to create a phony artifact would probably have done so. As it was, the strangeness of the characters and the direction of writing (or to be more precise, the direction in which the artisan wrote the letters) gives us something to think about. Juan Francisco, a respected Philippine paleographer, did some analysis of the letters in his 1973 book, Philippine Palaeography. He could not decipher the writing, however. His analysis mainly consisted of classifying the letters as curvilinear, lineo-angular, or a combination of the two. I cannot see the usefulness of such a classification because there is no benefit from its use, whether in trying to find the script's heritage or in classifying it among the known scripts of the world. His book contains good sketches of all the letters though, which makes the section on the Calatagan pot in his book not entirely useless. The writing on the pot goes around its mouth. The letters look similar to those of classic Philippine scripts (Tagalog, Tagbanwa, Buhid, and Hanunóo) but some appear to be oriented in strange ways. Some show a similarity to older scripts used in Indonesia, suggesting an earlier development of classic Philippine scripts. The symbols are divided by stop marks into six groups (which may be phrases), each consisting of five or seven symbols. Calatagan Writing What is strange and maybe significant about the writing is the apparent direction in which the artisan wrote it. A look at the pot will show that the artisan engraved the letters into the soft clay in a direction going to the left looking at the pot as it stands right side up. He apparently misjudged the length of the writing and ran out of space so that its last few letters go under the starting point. This gives us a clue as to the literacy of the artisan. We know that ALL Southeast Asian scripts share a common ancestor and were meant to be read and written from left to right. (Forget what others have said about having observed Tagbanwans writing on bamboo slats in a direction away from their body. You have seen classmates in … [Read more...]