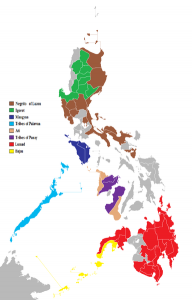

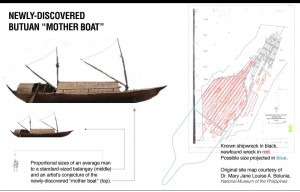

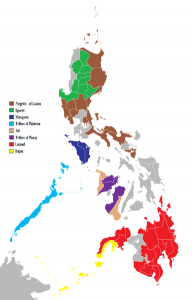

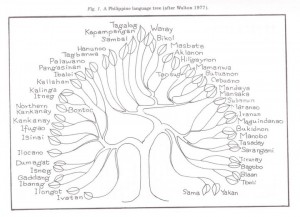

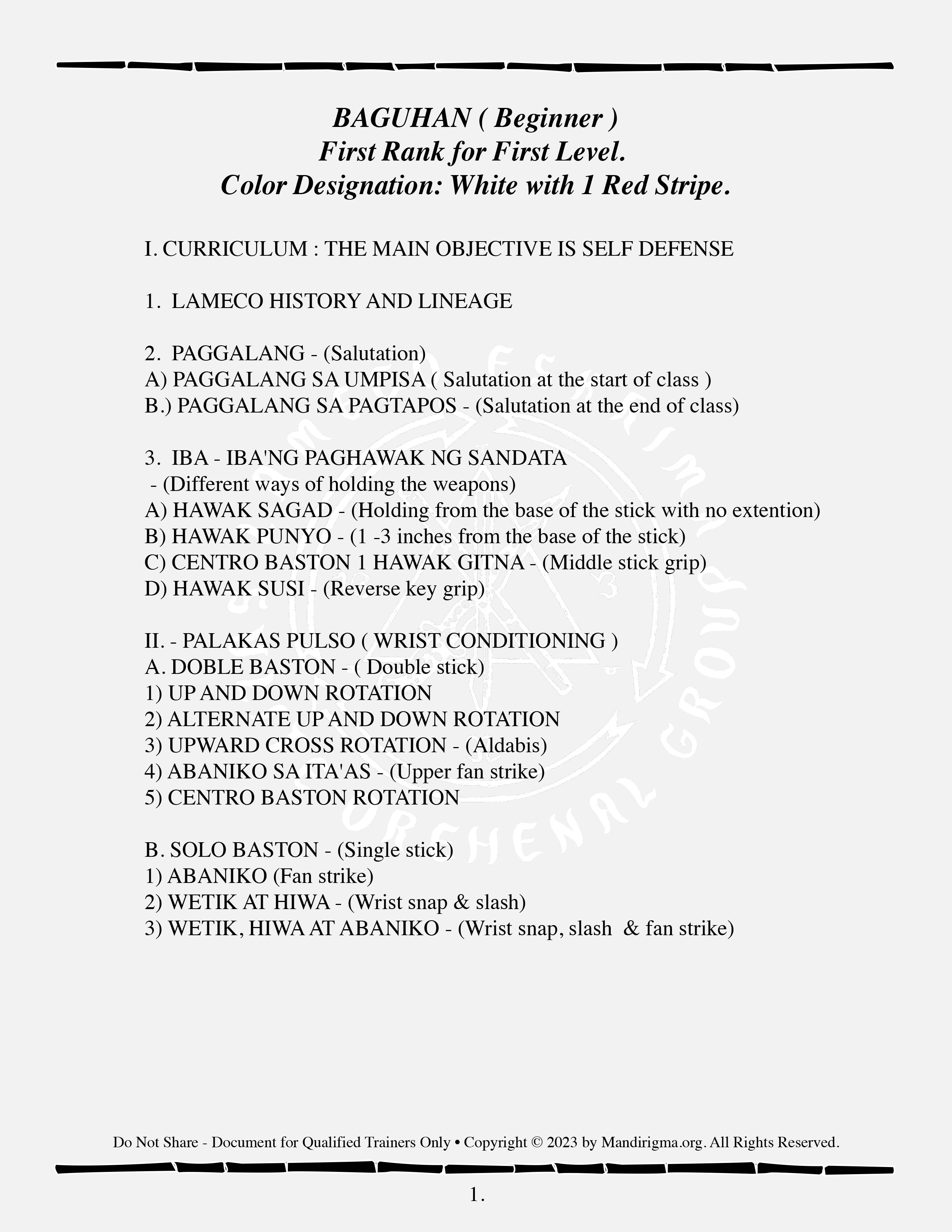

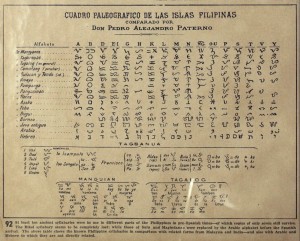

Original Article from Prehispanic CEBU: https://prehispaniccebu.wordpress.com/2020/11/02/surat-bisaya/?fbclid=IwAR0c3WbOE-USQB3V4Yy7paNkvV_qzKa-LyzrzOVYi1gaFFhlrSd9_bN4u5Y Prehispanic CEBU Glimpse of the past from prehistory to 16th century through the primary sources of Cebu’s antiquity. Surat Bisaya DBCantillas Etymology and Origins November 2, 2020 2 Minutes House Bill 1022 or the “National Writing System Act” was previously approved last April 23, 2018 and declares Baybayin as the country’s national writing system and thus aims to put the script to use in street signs, public facilities, government halls, publications and even food labels. Many linguists, historians and several Filipinos were upset that other Philippine scripts are ignored. Prehispanic writing system has enjoyed a resurgence over the past few years with some Filipinos taking interest in learning as their means of tracing one’s roots and connecting with one’s culture. Of our 17 accounted Philippine syllabaries, systems of consonant plus vowel syllables, only four (4) remain in use among indigenous communities of present-day according to UNESCO. Brahmic Scripts Prehispanic Philippine syllabaries are the writing systems that developed (and soon flourished) all over the Philippines. Many of the Southeast Asian writing systems clearly descended from ancient alphabets used in India over 2000 years ago. In the languages of Sumatra, Sulawesi as well as Philippines, the native name for letter, or script, is the indigineous term: surat. By the 21st century, various Filipino cultural organizations simply collectively referred the scripts as suyat. The country’s surat–or suyat–are related closely to other Southeast Asian writing, nearly all are abugidas or alpha-syllabary where any consonant is pronounced with the inherent vowel /a/ following it; using diacritical marks to express other vowels. It developed from South Indian Brahmi scripts utilized in Asoka Inscriptions and Pallava Grantha–type of writings during the ascendancy of India’s Pallava dynasty around the 5th century. Surat (Suyat) Baybayin does not encompass an entirety of writing systems being just one of those 17 prehispanic scripts present around the Philippines. Widespread use was likewise reported among other coastal-groups like the Bisaya, Iloko, Pangasinan, Bikol, and Pampanga in the 16th century. H.B. 1022 critics worry that relegating the Baybayin would erase the diversity that continue to exist and also perpetuate Tagalog-centric national identity. The Visayans have Surat Bisaya, Suwat Bisaya or Sulat Bisaya (aka Badlit; Surat is historically the more appropriate name for Visayan scripts). It is written from left to right and requires “no spaces” between words. Space is applied only after ends of a sentence or punctuation, although in its modern writing it usually contains spaces after each word to enhance readability of the narrative. Artifacts found with Surat inscriptions then deciphered through our Visayan language included the Calatagan Pot, Monreal Stones (two) and Limasawa Pot. When the Spaniards arrived, they studied and used surat to communicate with the early Filipinos; and teach Catholicism. As Filipinos soon started to learn the Roman alphabet from the Spanish, the use of our native scripts especially in lowland places began to disappear. Meanwhile, surat of Sulu and Maguindanao were replaced by the Arabic alphabet around the 14th and 15th centuries, respectively. Phonemes and Diacritics Surat Bisaya has 20 (originally from 18) phonemes: 15 primary consonants and 5 (from 3) vowels. Basic consonants (or sinugdanan na katingog)–b, k, d, g, h, l, m, n, ŋ (ng), p, r, s, t, w, j (y)–followed by inherent vowel /a/, are as follows: Ba, Ka, Da, Ga, Ha, La, Ma, Na, Nga, Pa, Ra, Sa, Ta, Wa, Ya. Five vowels (the pantingog) are: A, U, O, I, E. In prehispanic period, Bisaya only had three vowel-phonemes: /a/, /i/, and /u/. This was later expanded into five (5) with the introduction plus integration of some Hispanic-words: /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, and /u/. Kudlit (or diacritical marks) enables the writer to change the default /a/ sound of any of our basic consonants via using the same character. Put that kudlit below the syllable to change the consonants default vowel to /u/ or /o/, or above the syllable for /i/ or /e/. Spaniards even introduced to terminate consonants default vowel as well as various panulbok (“punctuation marks”). … [Read more...]