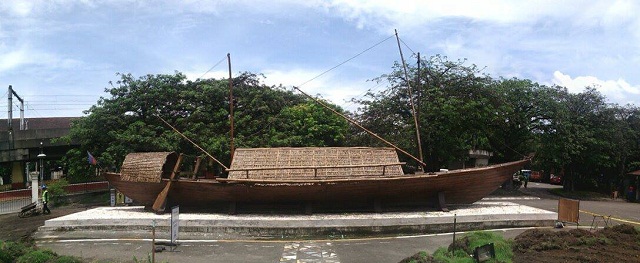

Massive balangay ‘mother boat’ unearthed in Butuan By TJ DIMACALI,GMA News

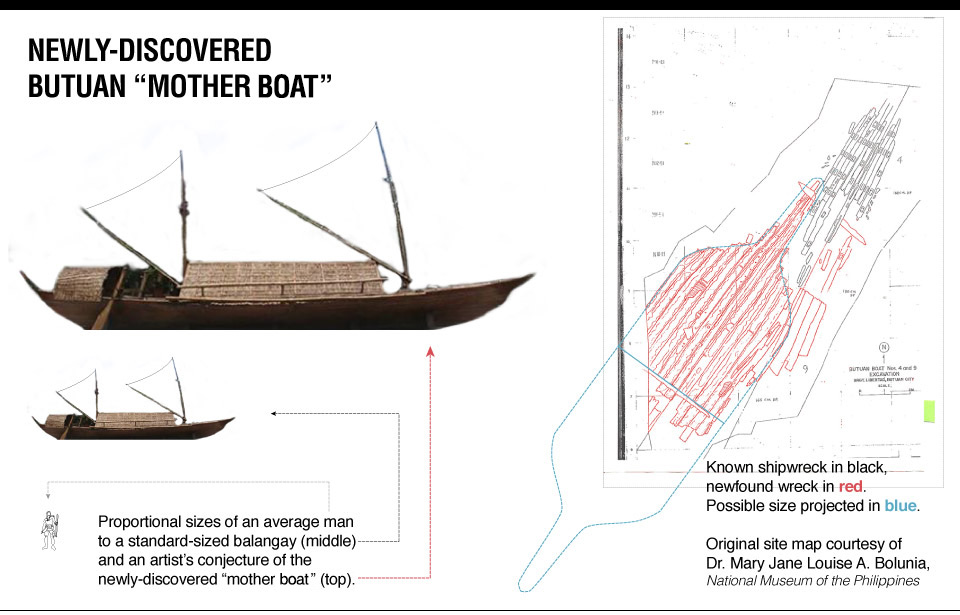

National Museum archeologist Dr. Mary Jane Louise A. Bolunia, who leads the research team at the site, says almost everything about the newly-discovered “balangay” is massive.She holds up her hand and curls her fingers into a circle, as if grasping a soda can. “That’s just one of the treenails used in its construction,” Bolunia says.

National Museum archeologist Dr. Mary Jane Louise A. Bolunia, who leads the research team at the site, says almost everything about the newly-discovered “balangay” is massive.She holds up her hand and curls her fingers into a circle, as if grasping a soda can. “That’s just one of the treenails used in its construction,” Bolunia says.

In fact, Filipino seafarers were already exploring Asia over a thousand years ago, well ahead of our Chinese neighbors: as early as 1001, the Song Dynasty recorded the arrival of a diplomatic mission from the “Kingdom of Butuan.”

“In 1003 AD, a Butuan chieftain petitioned the Chinese Imperial Court to allow it to bring its products direct to Guandong—instead of using Champa as the entrepôt (main trading post),” Azurin added.

However, according to Azurin, the petition was declined because the Court insisted on regulating trade via Champa.

He also says that Butuan may also have played a major role in the spread of culture and religion in the Philippines long before Christianity and even Islam came to the islands.

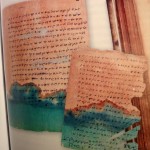

“The boat’s possible deeper significance is that it may be one of the carriers of Hindu-Buddhist cultural influence in the Philippine Archipelago long before Islam and Christianity arrived here. Many scholars also say that the baybayin script arrived here through the same connection with Champa. Hence, you can deepen the cultural legacy of our ancestors,” Azurin said.

Could Filipino craftsmen have been deployed from Butuan to build ancient Asian monuments, like Angkor Wat?

“That’s a possible conjecture, considering that archeologists like Robert Fox, H. Otley Beyer and others have pointed out that some islands in southern Philippines had communities linked to (these places),” he said.

Continuing a seaworthy tradition

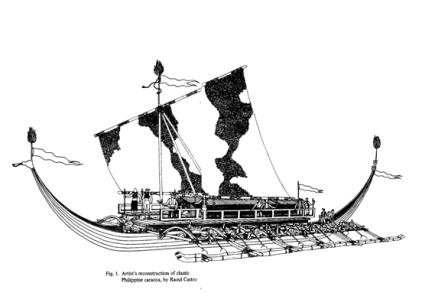

Scott also hinted at the existence of even more impressive vessels: “The most celebrated Visayan vessel was the warship called karakoa, (which) could mount forty (meter-long oars) on a side.”

Scott also hinted at the existence of even more impressive vessels: “The most celebrated Visayan vessel was the warship called karakoa, (which) could mount forty (meter-long oars) on a side.” Dr. Bolunia and her team plan to return to Butuan in September to complete the excavation, and hopefully to date the massive new find.

Dr. Bolunia and her team plan to return to Butuan in September to complete the excavation, and hopefully to date the massive new find.