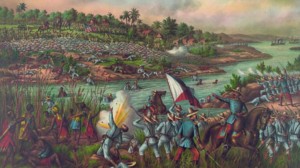

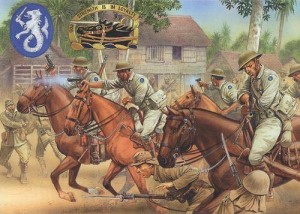

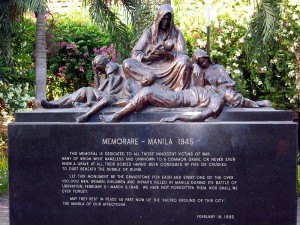

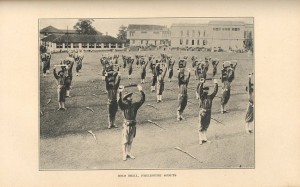

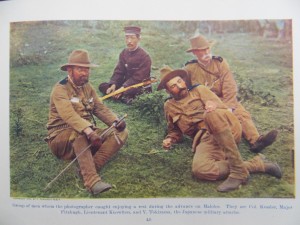

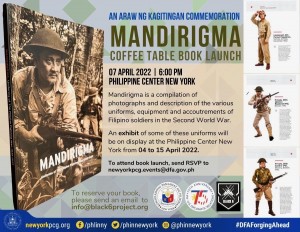

https://www.black6project.org/store-1/p/57s1rtjw9bglibetk0inieqfxai4ya Mandirigma - Uniforms of The Filipino Fighting Man 1935-1945 Mandirigma is a compilation of photographs and description of the various uniforms, equipment and accoutrements of Filipino soldiers in the Second World War. An exhibit of some of these uniforms will be on display at the Philippine Center of New York from April 4-15, 2022 Book availability can be picked up at the Philippine Consulate General of New York on April 7th during the book launch event at 8pm. When checking out, please choose PIck-Up or Delivery. Delivery $50 + 6 Shippng Pick Up $50 Pick-Up can be facilitated for you at the Philippine Consulate General of New York during the book launch event https://www.black6project.org/store-1/p/57s1rtjw9bglibetk0inieqfxai4ya … [Read more...]