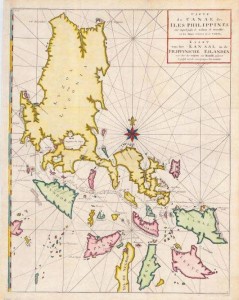

Who Discovered the Philippines? PerryScope Perry Diaz, Global Balita Philippine history books have been saying that Ferdinand Magellan discovered the Philippines. But was he really the one who discovered the Philippines? Long before Magellan landed in the Philippine archipelago, visitors and colonizers from other lands had come to our shores. The earliest evidence of the existence of modern man — homo sapiens sapiens — in the archipelago was discovered in 1962 when a National Museum team led by Dr. Robert Fox uncovered the remains of a 22,000-year old man in the Tabon Caves of Palawan. The team determined that the Tabon Caves were about 500,000 years old and had been inhabited for about 50,000 years. In the late 1990s, Jared Diamond, Professor of Geography at UCLA and winner of the Phi Beta Kappa Award in Science, and Peter Bellwood, Professor of Archaeology at the Australian National University, postulated that the Austronesians had their roots in Southern China. Diamond said that they migrated to Taiwan around 3,500 B.C. However, Bellwood believed that the Austronesian expansion started as early as 6,000 B.C. Around 3,000 B.C., the Malayo-Polynesians — a subfamily of the Austronesians — began their migration out of Taiwan. The first stop was northern Luzon. Over a span of 2,000 years, the Malayo-Polynesian expansion spread southward to the rest of the Philippine archipelago and crossed the ocean to Celebes, Borneo, Timor, Java, Sumatra, Malay Peninsula, and Vietnam; westward in the Indian Ocean to Madagascar; and eastward in the Pacific Ocean to New Guinea, New Zealand, Samoa, Fiji, Marquesas, Cook, Pitcairn, Easter, and Hawaii. Today, the Malayo-Polynesian speaking people have populated a vast area that covers a distance of about 11,000 miles from Madagascar to Hawaii, almost half the circumference of the world. In 2002, Bellwood and Dr. Eusebio Dizon of the Archaeology Division of the National Museum of the Philippines led a team that conducted an archaeological excavation in the Batanes Islands, which lie between Taiwan and Northern Luzon. The three-year archaeological project, financed by National Geographic, was done to prove — or disprove — the “Out of Taiwan” hypothesis for the Austronesian dispersal. The archaeological evidence that they gathered proved that the migration from Taiwan to Batanes and Luzon started about 4,000 years ago. For the next 500 years after the arrival of the Malayo-Polynesians in Batanes and Northern Luzon, native settlements flourished throughout the archipelago. The Philippine islands’ proximity to the Malay Archipelago, which includes the coveted Moluccas islands — known as the “Spice Islands” — had attracted Arab traders who had virtual monopoly of the Spice Trade until 1511. By the 9th century, Muslim traders from Malacca, Borneo, and Sumatra started coming to Sulu and Mindanao. In 1210 AD, Islam was introduced in Sulu. An Arab known as Tuan Mashaika founded the first Muslim community in Sulu. In 1450 AD, Shari’ful Hashem Syed Abu Bakr, a Jahore-born Arab, arrived in Sulu from Malacca. He married the daughter of the local chieftain and established the Sultanate of Sulu. In the early 16th century, Sharif Muhammad Kabungsuan, a Muslim preacher from Malacca arrived in Malabang in what is now Lanao del Sur and introduced Islam to the natives. In 1515 he married a local princess and founded the Sultanate of Maguindanao with Cotabato as its capital. By the end of the 18th century, more than 30 sultanates were established and flourished in Mindanao. The Sultanates of Maguindanao and Sulu were the most powerful in the region. Neither of them capitulated to Spanish dominion. Chinese traders — who were also involved in the Spice Trade — started coming to the Philippine archipelago in the 11th century. They went as far as Butuan and Sulu. However, most of their trade activities were in Luzon. In 1405, during the reign of the Ming Dynasty in China, Emperor Yung Lo claimed the island of Luzon and placed it under his empire. The Chinese called the island “Lusong” from the Chinese characters Lui Sung. The biggest settlement of Chinese was in Lingayen in Pangasinan. Lingayen also became the seat of the Chinese colonial government in Luzon. When Yung Lo died in 1424, the new Emperor Hongxi, Yung Lo’s son, lost interest in the colony and the colonial government was dissolved. However, the Chinese settlers in Lingayen — known as “sangleys” — remained and prospered. Our national hero Dr. Jose P. Rizal descended from the sangleys. The lucrative Spice Trade attracted the European powers. In 1511 a Portuguese armada led by Alfonso d’Albuquerque attacked Malacca and deposed the sultanate. Malacca’s strategic location made it the hub of the Spice Trade; and whoever controlled Malacca controlled the Spice Trade. At that time, Malacca had a population of 50,000 and 84 languages were spoken. It is interesting to note that in 1515, … [Read more...]