Macario Sakay: Tulisán or Patriot?

by Paul Flores

© 1996 by Paul Flores and PHGLA

All rights reserved

Contrary to popular belief, Philippine resistance to American rule did not end with the capture of Emilio Aguinaldo in 1901. There were numerous resistance forces fighting for Philippine independence until the year 1910. One of these forces was led by Macario Sakay who established the Tagalog Republic.

Born in 1870 in Tondo, Macario Sakay had a working-class background. He started out as an apprentice in a calesa manufacturing shop. He was also a tailor, a barber, and an actor in comedias and moro-moros. His participation in Tagalog dramas exposed him to the world of love, courage, and discipline.

In 1894, Sakay joined the Dapitan, Manila branch of the Katipunan. Due to his exemplary work, he became head of the branch. His nightly activities as an actor in comedias camouflaged his involvement with the Katipunan. Sakay assisted in the operation of the Katipunan press. During the early days of the Katipunan, Sakay worked with Andres Bonifacio and Emilio Jacinto. He fought side by side with Bonifacio in the hills of Morong (now Rizal) Province.

During the initial stages of the Filipino-American war, Sakay was jailed for his seditious activities. He had been caught forming several Katipunan chapters and preaching its ideals from town to town.

Republika ng Katagalugan

Released in 1902 as the result of an amnesty, Sakay established with a group of other Katipuneros the Republika ng Katagalugan in the mountains of Southern Luzon.

Sakay held the presidency and was also called “Generalisimo.” Francisco Carreon was the vice-president and handled Sakay’s correspondence. Julian Montalan was the overall supervisor for military operations. Cornelio Felizardo took charge of the northern part of Cavite (Pasay-Bacoor) while Lucio de Vega controlled the rest of the province. Aniceto Oruga operated in the lake towns of Batangas. Leon Villafuerte headed Bulacan while Benito Natividad patrolled Tanauan, Batangas.

In April 1904, Sakay issued a manifesto stating that the Filipinos had a fundamental right to fight for Philippine independence. The American occupiers had already made support for independence, even through words, a crime. Sakay also declared that they were true revolutionaries and had their own constitution and an established government. They also had a flag. There were several other revolutionary manifestos written by the Tagalog Republic that would tend to disprove the U.S. government’s claim that they were bandits.

The Tagalog Republic’s constitution was largely based on the early Katipunan creed of Bonifacio. For Sakay, the new Katipunan was simply a continuation of Bonifacio’s revolutionary struggle for independence.

Guerilla tactics

In late 1904, Sakay and his men took military offensive against the enemy. They were successful in seizing ammunition and firearms in their raids in Cavite and Batangas. Disguised in Philippine Constabulary uniforms, they captured the U.S. military garrison in Parañaque and ran away with a large amount of revolvers, carbines, and ammunition. Sakay’s men often employed these uniforms to confuse the enemy.

Using guerrilla warfare, Sakay would look for a chance to use a large number of his men against a small band of the enemy. They usually attacked at night when most of the enemy was looking for relaxation. Sakay severely punished and often liquidated suspected collaborators.

The Tagalog Republic enjoyed the support of the Filipino masses in the areas of Morong, Laguna, Batangas, and Cavite. Lower class people and those living in barrios contributed food, money, and other supplies to the movement. The people also helped Sakay’s men evade military checkpoints. They collected information on the whereabouts of the American troops and passed them on. Muchachos working for the Americans stole ammunition and guns for the use of Sakay’s men.

Unable to suppress the growth of the Tagalog Republic, the Philippine Constabulary and the U.S. Army started to employ “hamletting” or reconcentration in areas where Sakay received strong assistance. The towns of Taal, Tanauan, Santo Tomas, and Nasugbu in the province of Batangas were reconcentrated. This cruel but effective counter-insurgency technique proved disastrous for the Filipino masses. The forced movement and reconcentration of a large number of people caused the outbreak of diseases such as cholera and dysentery. Food was scarce in the camps, resulting in numerous deaths.

Meanwhile, search and destroy missions operated relentlessly in an attempt to suppress Sakay’s forces. Muslims from Jolo were brought in to fight the guerrillas. Bloodhounds from California were imported to pursue them. The writ of habeas corpus was suspended in Cavite and Batangas to strengthen counter-insurgency efforts. With support cut off, the continuous American military offensive caused the Tagalog Republic to weaken.

Fall of Sakay

While all of these were going on, the American leader of the Philippine Constabulary, Col. Harry H. Bandholtz, conceived a plan to deceive Sakay and his men. He would later be quoted as saying that the technique involved “playing upon the emotional and sentimental part of the Filipino character.”

In mid-1905, the American governor-general of the Philippines, Henry Ide, sent an ilustrado named Dominador Gomez to talk to Sakay. Gomez presented a letter from the American governor. The written statement promised that if Sakay surrendered, he and his men wouldn’t be punished or jailed. Moreover, Gomez assured Sakay that a Philippine Assembly comprising of Filipinos will be formed to serve as the “gate of kalayaan.”

Sakay took the bait, went down from the mountains, and surrendered on July 14, 1906.

On July 17, Sakay and his staff were invited to attend a dance hosted by the acting governor of Cavite. Just before midnight, they were surrounded, disarmed, and arrested by American officers who were strategically deployed in the crowd. Sakay and his men were brought to the Bilibid Prison. They were tried and convicted as bandits.

During the trial, Gomez was not around to produce the letter from the American governor-general. He didn’t even show up and the letter had mysteriously disappeared.

Sakay was hanged on September 13, 1907. Before he died, he uttered, “Filipinas, farewell! Long live the Republic and may our independence be born in the future!”

L to R: seated, Julian Montalan, Francisco Carreon, Macario Sakay, Leon Villafuerte; standing, Benito Natividad, Lucio de Vega.

Sakay and many of his followers favored long hair, certainly something strange for his era. This affectation may have been exploited by the Americans in their efforts to portray Sakay and his men as wild bandits preying on the simple folk of the countryside. Even today, many in the Tagalog area (most of whom have never heard of Macario Sakay) refer to a man with long hair as “someone who looks like Sakay.” This is, perhaps, a testimony to the effectiveness of the American propaganda campaign.

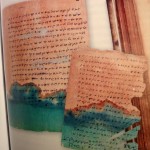

This vest with all its religious figures and Latin phrases belonged to Macario Sakay. It was his anting-anting and protected him from bullets and other hazards of war.

Many Filipinos who participated in the fight against Spain and the United States used anting-antings of all types for personal protection.

This is the author’s impression of what Sakay’s Republika ng Katagalugan flag must have looked like. There are no available pictures of the flag; this reconstruction was based on a written description.

Further reading:

1. Abad, Antonio K. General Macario L. Sakay: Was he a bandit or a patriot? Manila: J.B. Feliciano & Sons, 1955.

2. Constantino, Renato. The Philippines: A past revisited. Quezon City: Tala Publishing,1975.

3. Ileto, Reynaldo C. Pasyon and revolution: Popular movements in the Philippines, 1840-1910. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1979.

(This article was originally presented by the author to PHGLA on 8/12/95.)

To cite:

Flores, Paul. “Macario Sakay: Tulisán or Patriot?” in Hector Santos, ed., Philippine Centennial Series; at http://www.bibingka.com/phg/sakay/. US, 24 August 1996.

Flag Illustration from http://www.watawat.net/